Visual Art by Artani Paris | Pioneer in Luxury Brand Art since 2002

The home where you spent decades raising children and building memories may no longer serve your changing needs—stairs become obstacles, yard maintenance feels overwhelming, isolation replaces the neighborhood community you once knew. Yet the decision to move into senior housing feels monumental, loaded with questions: “Which type of community is right for me?” “Can I afford it?” “Will I lose my independence?” “What if I choose wrong?” This comprehensive guide cuts through the confusion surrounding senior housing in 2025, helping you understand your options clearly and choose wisely. You’ll learn the fundamental differences between independent living, assisted living, memory care, continuing care retirement communities, and active adult communities—what each provides, who they’re designed for, and realistic costs. We’ll explore how to evaluate communities systematically using objective criteria rather than impressive lobbies and sales pitches, understand contracts and financial commitments that protect your assets, identify red flags signaling poor-quality communities, and time your move optimally—neither too early (unnecessary expense and adjustment) nor too late (crisis-driven decisions with limited options). Whether you’re planning years ahead or need housing now due to health changes, this guide provides practical decision-making frameworks. You’ll discover how to tour communities effectively, ask questions that reveal truth beyond marketing, involve family in decisions without surrendering autonomy, and transition successfully to your new home. The right senior housing community enhances life quality, providing safety, social connection, services, and peace of mind—but only if you choose well.

Understanding Your Senior Housing Options

Senior housing isn’t one-size-fits-all. Multiple distinct types exist, each designed for different needs, capabilities, and preferences. Understanding these differences is critical to choosing appropriately.

Independent Living Communities: Designed for active seniors who don’t need assistance with daily activities but want maintenance-free living and social opportunities. What’s included—private apartment or cottage (studio to 2-bedroom typical), all maintenance (landscaping, exterior repairs, common area upkeep), some utilities (varies by community), housekeeping (weekly or bi-weekly), dining options (typically one or two meals daily in community dining room), social activities and events, transportation (scheduled trips to shopping, medical appointments, events), fitness center and wellness programs, emergency call systems in units. What’s NOT included—personal care assistance (bathing, dressing, medication management), medical care or nursing services, specialized dementia care. Who it’s for—seniors 55+ who are fully independent in all activities of daily living, want to downsize from larger homes, desire social community and activities, want to eliminate home maintenance burdens. Average costs 2025—$2,000-$4,500 monthly depending on location and amenities. Entry fees sometimes required: $100,000-$500,000 (partially refundable). Advantages—maintains independence while reducing home burdens, built-in social community combats isolation, predictable monthly expenses, ages in place to some degree. Disadvantages—expensive if you don’t utilize amenities, may need to move again if care needs increase, less privacy than single-family home, monthly fees increase annually (3-5% typical).

Assisted Living Communities: For seniors who need help with some daily activities but don’t require 24/7 nursing care. What’s included—everything from independent living PLUS personal care assistance (help with bathing, dressing, grooming, toileting, transferring), medication management (staff administer or remind), increased meal service (three meals daily typically), 24/7 staff availability, enhanced safety features, higher staff-to-resident ratios. Levels of care—most assisted living communities offer tiered care: Level 1 (minimal assistance, medication reminders), Level 2 (moderate assistance, help with bathing/dressing), Level 3 (substantial assistance, help with most activities). Cost increases with care level. Who it’s for—seniors who struggle with activities of daily living (ADLs) but don’t need skilled nursing, those with mobility limitations requiring assistance, individuals needing medication supervision, people at fall risk benefiting from closer monitoring. Average costs 2025—$4,500-$7,500 monthly for base level care. Additional care levels add $500-$2,000 monthly. Regulations—licensed and regulated by states. Must meet specific staff training, safety, and care requirements. Regular inspections. Advantages—personalized care as needs increase, more affordable than nursing homes for similar care levels, maintains dignity and independence with support. Disadvantages—expensive, not covered by Medicare (some Medicaid coverage after spend-down), less independence than independent living, must move to nursing home if medical needs exceed assisted living capabilities.

Memory Care Communities: Specialized care for those with Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, or other cognitive impairments. What makes them different—secured environment preventing wandering, staff specially trained in dementia care, structured routines reducing confusion and anxiety, memory-enhancing activities, lower resident-to-staff ratios (often 4-6 residents per caregiver), sensory rooms and therapeutic programming, family support and education. Who needs memory care—diagnosis of dementia or Alzheimer’s requiring supervision, wandering behavior making home unsafe, behavioral issues (aggression, sundowning) requiring specialized management, caregiver burnout where family can no longer provide safe care. Average costs 2025—$6,000-$10,000 monthly depending on location and care intensity. Among most expensive senior housing options. Funding—Medicare doesn’t cover. Long-term care insurance may cover. Medicaid covers in some facilities after spend-down. When to consider—earlier rather than later in dementia progression often easier—person adapts while still capable of some adjustment. Crisis placements (after fall, hospitalization, emergency) more traumatic. Advantages—specialized care improving quality of life for dementia patients, safety and security, family relief from 24/7 caregiving burden. Disadvantages—extremely expensive, emotionally difficult transition, locked environment feels restrictive to some.

Continuing Care Retirement Communities (CCRCs): Also called Life Plan Communities—provide continuum of care from independent living through nursing care on one campus. How they work—you move in while independent, live in independent apartment/cottage. If care needs increase, move to assisted living section of same campus. If nursing care needed, nursing facility on-site. Remain in same community throughout aging process. Contract types—Life Care (extensive) contracts: large upfront fee ($200,000-$1,000,000+) plus monthly fee ($2,000-$5,000). Guarantees all future care levels at little or no cost increase. Modified contracts: lower upfront fee, monthly fees increase significantly if care needs increase. Fee-for-service contracts: lowest upfront fee, pay market rates for care as needed. Who it’s for—seniors planning long-term who want to age in place without future moves, those with assets for substantial entry fees, people wanting predictability and security. Average costs 2025—highly variable. Entry fees $100,000-$1,000,000. Monthly fees $2,000-$6,000. Total lifetime cost $300,000-$1,500,000+. Advantages—never have to move again, spouse can stay on campus even if care needs differ, locks in future care costs (life care contracts), built-in continuum of care. Disadvantages—massive upfront investment, long waiting lists (1-2 years typical for popular communities), strict admission requirements (health, financial), lose investment if you leave early or die soon after entry.

Active Adult Communities (55+ Communities): Age-restricted housing for independent, active seniors—NOT care facilities. What they are—private homes (single-family, townhomes, condos) in age-restricted neighborhoods (at least one resident 55+, no permanent residents under 18-19). What’s included—home ownership or rental, community amenities (clubhouse, pools, golf, fitness center, activities), homeowners association maintaining common areas and organizing events. What’s NOT included—no care services, no medical support, no assisted living features. These are neighborhoods, not care communities. Who it’s for—active, independent 55+ adults wanting adult-only community, those desiring resort-style amenities and social activities, people downsizing from family homes but not needing care. Average costs 2025—home purchase: $150,000-$500,000+ depending on location. HOA fees: $100-$500 monthly. Own and maintain your home. Examples—Del Webb Sun City communities, The Villages in Florida, Leisure World communities. Advantages—home ownership (build equity), adult environment (no children noise), extensive amenities, active social life, usually lower cost than continuing care communities. Disadvantages—no care services if needs change (must move), still responsible for home maintenance, HOA fees and restrictions, may feel isolated if you’re younger/more active than typical residents.

| Community Type | Independence Level Required | Care Services | Average Monthly Cost | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Adult (55+) | Fully independent | None | $1,500-$3,000 (mortgage/HOA) |

Active seniors wanting amenities, no care needs |

| Independent Living | Fully independent | None (emergency only) | $2,000-$4,500 | Maintenance-free living, social community |

| Assisted Living | Needs help with ADLs | Personal care, medication management | $4,500-$7,500 | Limited mobility, needs daily assistance |

| Memory Care | Cognitive impairment | Specialized dementia care, 24/7 supervision | $6,000-$10,000 | Alzheimer’s, dementia, wandering risk |

| CCRC (Independent) | Currently independent | None initially, full continuum available | $2,000-$5,000 (+ entry fee) |

Long-term planning, aging in place |

| Skilled Nursing | Requires medical care | 24/7 nursing, medical care, rehabilitation | $8,000-$15,000 | Post-surgery, chronic illness, end-of-life |

Evaluating Location and Community Features

Beyond housing type, location and specific community features dramatically impact your satisfaction and quality of life. Some factors are obvious, others easily overlooked until you live there.

Geographic Location Considerations: Proximity to family—single most important factor for many seniors. Being near adult children or grandchildren facilitates regular visits, emergency assistance, and family involvement in care. Long-distance family relationships are possible but challenging—consider honestly how often they’ll visit if you’re 1,000 miles away. Climate and weather—warm climates (Florida, Arizona, Southern California) attract retirees seeking mild winters. However: extreme summer heat challenges some seniors, hurricanes (Florida/Gulf Coast), wildfires (California), higher costs in popular retirement areas. Cold climates present different challenges: icy conditions and fall risk, snow removal needs, limited outdoor activity in winter, but often lower costs and closer to adult children in northern states. Cost of living—senior housing in San Francisco, New York, Boston costs 50-100% more than equivalent communities in smaller cities or different regions. $5,000 monthly gets luxury accommodations in North Carolina; basic accommodations in coastal California. Your retirement income stretches much further in low-cost areas. Healthcare access—proximity to quality hospitals, medical specialists, and emergency care increasingly important as you age. Rural communities may offer affordable, peaceful living but require 30+ minute drives to hospitals. Urban/suburban areas provide better medical access but higher costs. Cultural and social fit—moving to unfamiliar region means building new social connections from scratch—challenging for many seniors. Staying in familiar area maintains existing friendships, knows the community, understands local culture.

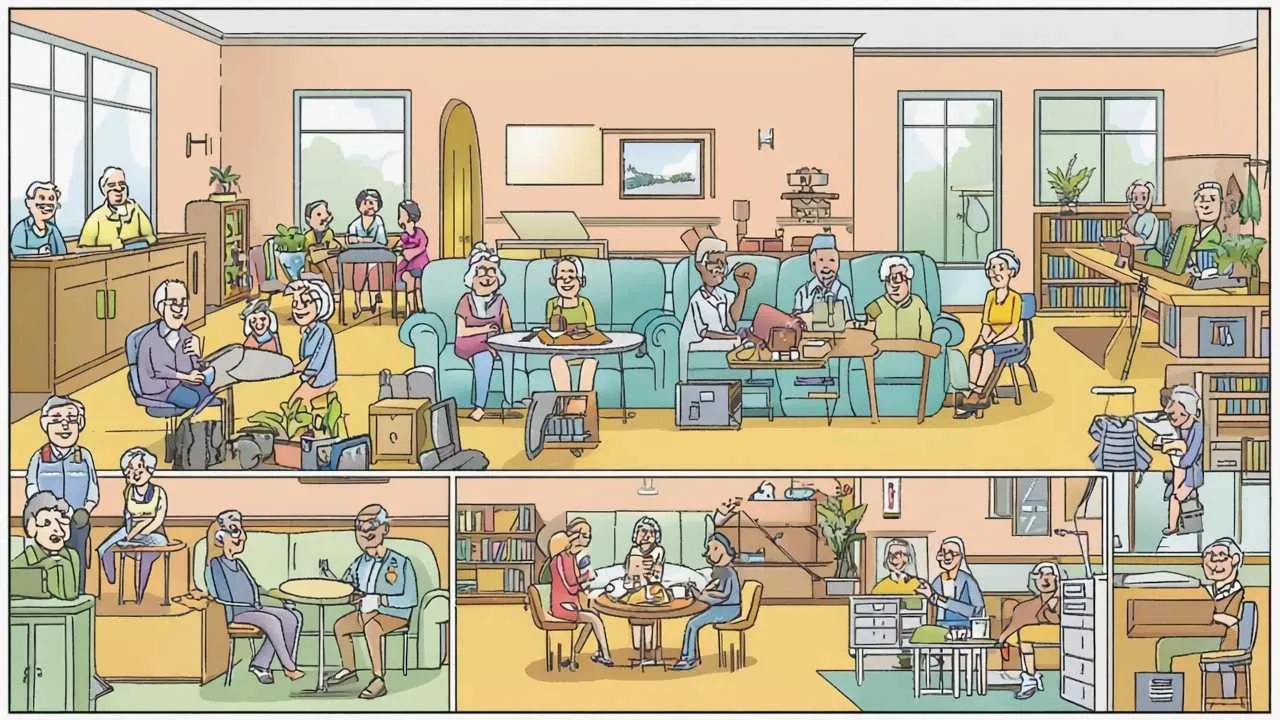

Community Size and Atmosphere: Small communities (30-80 residents)—more intimate, everyone knows each other, family-like atmosphere, easier to make close friendships, less anonymity (some find comforting, others find intrusive), limited activity variety, fewer amenities, may feel isolated if personality conflicts arise. Medium communities (80-200 residents)—balance of community and privacy, broader range of activities and social groups, enough residents to find compatible friends, still manageable size where staff knows you. Most popular size. Large communities (200+ residents)—extensive amenities (multiple dining venues, large fitness centers, diverse activities), more anonymity if desired, higher likelihood of finding compatible social group, can feel institutional or overwhelming, easier to become isolated despite large population. Culture and values—some communities emphasize: active lifestyle (daily fitness classes, outings, events), intellectual pursuits (book clubs, lectures, cultural events), faith-based community (affiliated with religious organization, chapel services, spiritual programming), LGBTQ+ friendly (explicitly welcoming, inclusive policies, SAGE-certified), affordability focus (simpler amenities, lower costs). Visit multiple times—eat meals with residents, attend activities, observe interactions. Community “feel” apparent only through experience, not brochures.

Essential Amenities and Services: Dining services—quality, variety, and flexibility matter enormously since you’ll eat there daily. Evaluate—menu variety (repetitive menus get boring), dietary accommodations (low-sodium, diabetic, vegetarian, religious restrictions), meal times flexibility (fixed or flexible seating?), dining atmosphere (institutional cafeteria vs. restaurant-style), guest meals (can family join? extra cost?), alternative dining options (café, bistro, private dining for family events), room service for ill days. Eat multiple meals during tour—lunch and dinner to assess quality consistency. Transportation—since many residents no longer drive, community transportation is lifeline. Assess—scheduled shopping trips (grocery, pharmacy, retail), medical appointment transportation (how far? what providers?), cultural/entertainment outings (restaurants, theater, museums), frequency (daily, weekly?), cost (included or extra fee per trip?), vehicle accessibility (wheelchair lifts?), spontaneous trips (can you request special transportation?). Activities and engagement—robust activity programming prevents boredom and isolation. Look for—variety (fitness, arts, education, social, spiritual, outings), frequency (daily options vs. weekly), optional participation (not forced), resident-driven options (can residents propose activities?), intergenerational programs (visits from local schools, youth groups), volunteer opportunities. Warning sign—limited activities dominated by bingo and TV watching suggests low-quality programming. Fitness and wellness—maintaining physical health critical for aging well. Evaluate—fitness center quality (just treadmills or comprehensive equipment?), group fitness classes (variety and frequency), personal training availability, pool (lap swimming vs. recreation), walking paths (indoor and outdoor for all weather), wellness programming (health screenings, nutrition education).

Visual Art by Artani Paris

Understanding Costs and Financial Considerations

Senior housing represents significant financial commitment—often consuming substantial portion of retirement savings. Understanding all costs (not just advertised rates) and funding options is critical.

Entry Fees and Deposits: Security deposits—independent living and assisted living typically require security deposits of $500-$5,000, fully refundable when you leave (minus damages). Community fees—some charge one-time community fee ($1,000-$5,000) for admissions processing, not refundable. CCRC entry fees—much larger: $100,000-$1,000,000+. Structure varies: Fully refundable (90-100% returned to estate when you leave or die—higher monthly fees compensate), partially refundable (50-90% returned—most common), declining refund (decreases 1-2% monthly until reaching floor like 50%, stabilizes there), non-refundable (sometimes called “Life Care” fee—lowest monthly costs but lose entire entry fee). Critical question—what happens to entry fee if you leave within first year? First five years? When you die? Get written explanation of refund schedule. Financial requirements—CCRCs often require proof of assets beyond entry fee: 2-3× entry fee plus 2-3 years of monthly fees in liquid assets. Example: $300,000 entry fee might require $600,000-$900,000 plus $72,000-$108,000 (assuming $3,000/month × 24-36 months) = $672,000-$1,008,000 total assets to qualify. Ensures you can afford community long-term.

Monthly Fees and What They Cover: Base monthly fee—covers specific services listed in contract. Read carefully—what’s included vs. additional cost? Typically included—apartment/cottage, maintenance, utilities (varies—some include all, others just some), basic housekeeping, certain meals, activities, transportation, emergency call system. Typically NOT included—phone/internet/cable (some communities bundle, others require separate accounts), guest meals, extra housekeeping beyond basic, special transportation beyond scheduled trips, beauty salon/barber, personal care supplies. Care level fees (assisted living)—base fee covers housing and services. Care fees added based on needs assessment: Level 1 care: +$500-$1,000 monthly, Level 2 care: +$1,000-$2,000 monthly, Level 3 care: +$2,000-$3,500 monthly. Annual increases—monthly fees increase annually. Typical—3-5% yearly, occasionally higher. $4,000/month becomes $4,120-$4,200 year two, $4,244-$4,410 year three, etc. Over 10 years at 4% annual increases, $4,000 becomes $5,920. Budget accordingly—use conservative estimate like 5% annual increases for long-term planning.

Funding Your Senior Housing: Home sale proceeds—most common funding source. Selling family home provides entry fees and initial years of monthly costs. Average home sale: $300,000-$400,000 in many markets. After selling costs (6-8% realtor fees, repairs, closing costs), net $275,000-$370,000. Funds CCRC entry fee or 5-8 years of independent/assisted living monthly costs. Retirement savings—401(k)s, IRAs, other investments supplement home proceeds. Strategy—use home sale for entry fees/initial costs, retirement savings for monthly fees. Withdrawal from retirement accounts for senior housing counts as taxable income—plan accordingly. Long-term care insurance—if you purchased long-term care insurance, it may cover assisted living or memory care costs. Typical coverage—$4,000-$6,000 monthly benefit, 3-5 year benefit period, 90-day elimination period (you pay first 90 days). Review policy carefully—some cover only nursing homes, not assisted living. Some require specific care levels. Contact insurance company before choosing community—verify coverage. Medicaid—covers some assisted living and nursing home care after spend-down. Spend-down requirement—must exhaust most assets (typically to $2,000-$15,000 depending on state) before Medicaid eligibility. Community must accept Medicaid (many don’t, or limit Medicaid beds). Reality—middle-class seniors often spend-down life savings paying for senior housing before Medicaid eligibility. Veterans benefits—Aid and Attendance benefit provides $2,431/month (2025) for single veteran, $2,896/month for couple if wartime veteran needs assistance with ADLs. Helps offset assisted living costs. Complex application process—contact VA or veterans service organization for help.

Budgeting for Senior Housing Long-Term: Calculate affordable monthly payment—total retirement income (Social Security, pensions, annuities, investment withdrawals) minus other fixed expenses (insurance, taxes, car, personal spending, emergency buffer) = amount available for housing. Example—$5,000 monthly income minus $1,500 other expenses = $3,500 affordable for housing. Reality check—can you afford this payment for 10-20+ years with 3-5% annual increases? $3,500 today becomes $4,025-$5,700 in 10 years. If not sustainable, consider less expensive community or geographic area. Emergency financial cushion—maintain 12-24 months of senior housing costs in accessible savings beyond what you’ve budgeted. Covers unexpected health expenses, temporary market downturns affecting income, or increased care needs. For $4,000 monthly housing cost, that’s $48,000-$96,000 emergency fund. Estate considerations—CCRC entry fees significantly reduce inheritance to children. $500,000 entry fee (even 90% refundable) means $500,000 less investment growth. If you die after 5 years, 90% refund returns $450,000—but opportunity cost of keeping $500,000 invested at 6% for 5 years is $169,000 lost growth. Discuss with family if leaving inheritance is priority.

Red Flags and Warning Signs to Avoid

Not all senior communities provide good care or ethical business practices. Recognizing warning signs protects you from poor choices—financially and physically.

Financial and Contract Red Flags: Pressure tactics—”limited spots available,” “prices increasing next month,” “special deal today only” are sales manipulation. Legitimate communities allow time for decision-making. Never sign anything during initial tour. Non-refundable deposit before reviewing contract—ethical communities provide contract for review by you and attorney before requiring payment. If they demand deposit to “hold your spot” before contract review, walk away. Vague contract terms—contracts should specify exactly: what’s included in monthly fee, what costs extra, refund terms for entry fees, conditions under which you can be asked to leave, fee increase limitations. Vague language (“amenities subject to change,” “fees may be adjusted”) without specifics is red flag. No financial transparency—reputable communities provide financial statements showing fiscal health. CCRCs especially should provide audited financials. Refusal suggests financial instability. Recent management company changes—frequent ownership/management turnover often indicates financial or operational problems. Research community’s ownership history. Deferred maintenance—worn carpets, peeling paint, broken equipment signals financial struggles or neglectful management. If they can’t maintain common areas, what about care quality?

Care Quality and Safety Red Flags: Insufficient staffing—during tour, observe staff-to-resident ratios. Are staff rushed? Residents waiting long periods for assistance? Call lights unanswered? High resident-to-staff ratios (over 12:1 in assisted living) suggest inadequate care. Visit during evening/weekend—staffing often reduced during these times. If community discourages off-hours visits, red flag. Unhappy or poorly treated staff—staff turnover rate is critical indicator. High turnover (over 50% annually) common in poor-quality communities. Ask staff how long they’ve worked there. If everyone is new, concern. Observe how management treats staff—disrespectful treatment of staff predicts poor resident care. Residents’ appearance and demeanor—observe residents during tour. Do they appear well-groomed and appropriately dressed? Are they engaged in activities or sitting alone staring? Do they seem happy or withdrawn? Are wheelchairs positioned so residents can participate in activities or parked facing walls? Odors—persistent urine smell in assisted living or memory care suggests inadequate toileting assistance and cleaning. Occasional accidents are normal; pervasive odor indicates systemic problem. Locked doors and residents attempting to leave—in memory care, secured entrances are appropriate. But residents constantly trying to exit or appearing distressed about confinement may indicate poor dementia care practices—inadequate engagement and activities leading to agitation. Pressure to upgrade care level prematurely—some communities push residents to higher (more expensive) care levels before truly needed to increase revenue. Get independent assessment from your doctor before accepting care level increase recommendations.

Researching Community Reputation: State licensing and inspection reports—assisted living facilities and nursing homes are licensed and inspected. Most states post inspection reports online. Search “[state name] assisted living inspection reports” or check state Department of Health website. Look for—number and severity of violations (minor paperwork issues vs. serious care deficiencies), repeat violations (same problems persisting despite citations), whether violations were corrected, complaints filed by residents/families. Online reviews—Google reviews, caring.com, Senioradvisor.com provide resident and family perspectives. Approach skeptically—very happy and very angry people review disproportionately. Look for patterns across multiple reviews rather than single extreme review. Common complaints worth noting—staffing shortages, poor food quality, lack of activities, difficulty getting management response, surprise fees, aggressive care level upgrades. Common positive themes—caring staff, engaged activities director, responsive management, good food, genuine community feel. Talk to current residents and families—during tour, ask to speak with residents without staff present. Ask families in lobby or parking lot about their experience. Questions to ask—”Would you choose this community again?” “What surprised you after moving in?” “How has management handled problems?” “Has care quality changed since you arrived?”

Touring and Evaluating Communities Effectively

A single morning tour with sales director provides limited, curated view of community. Effective evaluation requires multiple visits using systematic approach.

Planning Your Tour Strategy: Initial tour—start with scheduled tour led by community staff. This provides overview of community, shows model apartments, explains services and costs, answers basic questions. Take notes—bring notebook or use phone to record impressions, costs, specific features. Touring multiple communities, details blur without notes. Don’t make decisions during initial tour—resist pressure. Thank them, take materials, say you’ll think about it. Unannounced visit—after initial tour, return unannounced during different time (evening, weekend). Walk common areas, observe activities (or lack thereof), talk to residents without sales staff present. Communities putting “best foot forward” during scheduled tours reveal reality during unplanned visits. Meal visit—arrange to eat lunch or dinner as guest (usually allowed for fee). Sit with residents, ask about food quality, observe dining atmosphere, listen to conversations. Residents often share honest perspectives during meals. Activity participation—attend community event open to guests (concert, lecture, craft class). Observe resident participation and engagement, assess activity quality and variety, meet residents in relaxed setting. Overnight stay—some communities offer guest suites where potential residents can stay overnight. Invaluable experience—hear nighttime noise levels, experience emergency call system, eat breakfast, observe morning routines. Bring family member or friend—second opinion valuable. They may notice things you miss or ask questions you don’t think of. But ensure you maintain decision-making authority—your needs matter most.

Questions to Ask During Tours: Financial—”Explain exactly what’s included in base monthly fee and what costs extra.” “What has been average annual fee increase last 5 years?” “What happens to my entry fee if I leave after 1 year? 5 years? If I die?” “What are your financial qualifications—assets required?” “Can I see your most recent audited financial statement?” Care and services—”What is your staff-to-resident ratio during day? Evening? Overnight?” “How do you assess care needs and determine care levels?” “How often are care assessments updated?” “What happens if my care needs exceed what you can provide?” “Do you have RNs on staff or just CNAs?” Contracts and policies—”Under what circumstances can you require me to leave?” “How much notice must I give if I want to leave voluntarily?” “Can I see a sample contract to review with my attorney?” “What is your refund policy if I’m unhappy?” Community operations—”What is your staff turnover rate?” “How long has current executive director been here?” “Are there any planned fee increases or construction projects?” “What is your policy on Medicaid residents if I eventually need to spend down?” Quality of life—”How do you handle roommate conflicts or personality clashes?” “Can I bring my pet?” (if applicable) “What COVID or illness outbreak protocols do you follow?” “How do you include residents in community decisions and feedback?”

Comparing Multiple Communities: Create comparison spreadsheet—tour 3-5 communities, compare systematically. Categories to compare—base monthly cost, care level costs (if assisted living), entry fees and refund terms, included services vs. extra costs, apartment size and features, dining quality (your subjective assessment), activity variety and frequency, staff demeanor and engagement, resident satisfaction (your impression from conversations), location convenience (proximity to family, medical), overall atmosphere and culture, inspection report findings, financial stability. Weight factors by importance—what matters most to you? Cost? Proximity to family? Activity programming? Dining quality? Assign importance ratings (1-10) to each factor, then score each community on each factor. Calculate weighted scores. This systematic approach prevents emotional decision-making based on impressive lobby or charming sales director. Revisit top 2-3 choices—after initial evaluation, narrow to finalists. Visit each again, spending several hours. Bring family for their input. Try to visualize yourself living there—can you picture it? Does it feel right?

Visual Art by Artani Paris

Timing Your Move and Making the Transition

When you move into senior housing matters enormously—too early wastes money and independence, too late results in crisis-driven poor decisions.

Optimal Timing for Senior Housing: Move while independent (proactive approach)—research shows seniors moving into senior housing while still healthy and independent adapt more successfully than those forced by crisis. Advantages—time to research and choose carefully (not emergency decision), easier physical and emotional adjustment, establish friendships and routines before needing assistance, qualify for independent living (less expensive than assisted living), maintain sense of control over decision. Disadvantages—may feel premature—”I don’t need this yet,” expensive years before care services needed, leaving familiar home and community earlier than necessary. Ideal timing indicators—home maintenance becoming burdensome, social isolation increasing (friends moved or died, transportation challenges limiting activities), minor health concerns suggesting future care needs likely, age 75-80 for many (healthy enough to adjust, early enough to avoid crisis). Crisis-driven moves (reactive approach)—many seniors delay until health emergency forces decision: hospitalization, serious fall, dementia diagnosis, spouse death leaving survivor unable to manage alone. Disadvantages—limited time to research (may accept first available option), family often makes decisions without full senior input, adjustment more difficult during health crisis, may require assisted living immediately (more expensive), higher stress for everyone. Sometimes unavoidable—not all situations permit proactive planning. But when possible, planning ahead dramatically improves experience.

The Move Itself: Downsizing challenges—moving from 2,000-3,000 sq ft home to 600-900 sq ft apartment requires significant downsizing. Strategy—start 6-12 months before move: sort belongings into keep, donate, sell, trash categories. Keep only what fits comfortably in new space plus has emotional significance. Take floor plan of new apartment furniture shopping—mark tape on floor showing apartment dimensions and visualize furniture placement. Hire estate sale company or senior move manager if overwhelmed—they handle entire process. Emotional challenges—leaving home filled with memories causes grief. Normal to feel—sadness, anger, resentment (especially if move not your choice), anxiety about change, guilt about leaving (if spouse passed away in home), loss of identity tied to home and neighborhood. Coping strategies—allow yourself to grieve, take photos of home and favorite spaces before leaving, bring familiar items (furniture, art, photos) making new space feel like home, maintain connections with old neighbors and friends, give yourself 3-6 months to adjust before judging whether move was right. Physical move day—many communities have protocols: designated move-in days and times (to avoid multiple moves simultaneously), loading dock and freight elevator procedures, cleaning and setup requirements. Hire professional movers experienced with senior moves—they pack, move, unpack, set up furniture, hang pictures, make bed. Worth the cost ($1,000-$3,000) to reduce stress.

Adjusting to Community Living: First 3 months are hardest—expect adjustment period. Studies show most seniors report satisfaction with move after 6 months, but first few months challenging. Common initial frustrations—missing privacy and quiet of own home, scheduled mealtimes feel restrictive, sense of loss of independence, difficulty making friends (especially for introverts), community rules and regulations feel controlling, comparing new home unfavorably to old home. Strategies for successful adjustment—attend activities even if you don’t feel like it—social connection prevents isolation, invite family to visit frequently in first months—familiar faces provide comfort, give yourself permission to feel sad—doesn’t mean you made wrong choice, take advantage of services and amenities—you’re paying for them, be patient with yourself and community—adjustment takes time, talk to other residents about their adjustment experiences—you’ll find you’re not alone. Making friends—friendships form through repeated casual contact. Ways to meet people—eat meals in dining room rather than in apartment, sit at different tables to meet various residents, attend multiple activities (eventually find people with shared interests), volunteer for community committees or activities, invite neighbors for coffee or meal in your apartment, participate in group fitness classes, join or start a club based on your interests. When to worry—if after 6 months you’re still miserable, seriously isolated, or regretting move, reassess. Sometimes community truly isn’t right fit—better to acknowledge and move than force unsuccessful situation.

Real Success Stories

Case Study 1: Portland, Oregon

Margaret and Harold Chen (73 and 75 years old)

The Chens lived in 3-bedroom suburban home for 42 years—raised three children there, countless memories. But last 5 years became increasingly difficult: yard maintenance Harold once enjoyed now exhausted him, stairs to second-floor bedrooms challenging for Margaret’s arthritic knees, house felt empty and lonely after children moved across country, social isolation growing as longtime friends moved to senior communities or passed away, winter snow shoveling dangerous at their age.

They resisted adult children’s suggestions to move to senior housing: “We’re not old enough for that.” “This is our home.” “Assisted living is for people who can’t care for themselves—we’re fine.” Crisis came when Harold had minor stroke requiring brief hospitalization. Recovery fine, but event crystallized vulnerability—what if Margaret had been alone and unable to call for help?

They toured 5 independent living communities over 3 months. Chose mid-sized (120-unit) community 15 minutes from daughter, 30 minutes from son. Reasons: location near family, robust activity programming (Harold enjoyed woodworking workshop, Margaret wanted art classes), excellent dining (they ate three meals there during evaluation), transparent financials and contract, residents seemed genuinely happy, beautiful walking paths and gardens, fitness center with pool (Margaret’s doctor recommended aquatic therapy for arthritis).

Move was emotionally wrenching—selling family home felt like betraying memories. Downsizing from 2,400 sq ft to 850 sq ft two-bedroom apartment required letting go of 50+ years of accumulated possessions. First month in community, Margaret cried daily, Harold withdrew and sullen.

Results after 18 months:

- Both now say move was best decision they made—took 6 months to genuinely feel this way

- Health improved dramatically—Margaret’s arthritis pain reduced (daily pool exercise, no more stair climbing), Harold’s blood pressure normalized (regular fitness classes, stress reduction)

- Social life flourished—made 8-10 close friends, participate in 5-7 activities weekly, started new hobbies (Harold woodworking again, Margaret painting)

- Family relationships improved—children visit more often (comfortable guest suite in community), video calls easier (community has high-speed internet in apartments), less family worry about parents’ safety

- Freedom from home maintenance liberating—no more yard work, repairs, snow removal giving them time and energy for enjoyment

- Financial clarity reduced stress—predictable monthly cost (versus unpredictable home repairs), budgeting easier

- Peace of mind about future—as care needs increase, assisted living available on same campus; won’t have to move again

“The first three months, I hated it. I mourned our home, our neighborhood, our independence. I felt like we gave up. But around month four, something shifted. I started recognizing people in the dining room and actually looking forward to meals with friends. Harold joined a woodworking group and came alive again—he’d been depressed since retiring but wouldn’t admit it. By six months, I realized this wasn’t giving up—it was gaining a community we’d lost when our neighborhood aged and everyone moved or died. Now? I’d never go back. Our old house was full of memories but empty of life. This community is full of life.” – Margaret Chen

Case Study 2: Boca Raton, Florida

Robert “Bob” Sullivan (79 years old, widower)

Bob’s wife Linda passed away after 3-year battle with Alzheimer’s. He cared for her at home until final 6 months when memory care became necessary. After her death, Bob was exhausted, depressed, and alone in home that felt haunted by memories of Linda’s decline.

Adult son (living in Boston) worried about Bob’s isolation and declining self-care—Bob stopped cooking (living on frozen dinners), skipped showers, ignored house maintenance, rarely left home. Son flew to Florida, insisted they tour senior communities together. Bob resistant: “I’m fine. Leave me alone.” But agreed to look “just to get you off my back.”

Toured 4 communities. Bob critiqued everything: “Food’s not as good as Linda’s cooking.” “Activities are juvenile.” “I don’t need babysitting.” But at third community, something shifted. Resident woodshop had extensive equipment—Bob had been passionate woodworker before Linda’s illness consumed all his time and energy. Activities director said, “We have openings in woodworking club if you’re interested.” Bob lit up briefly, then caught himself: “I’m just looking.”

Son pushed gently: “Dad, try it for 6 months. If you hate it, you can leave.” Bob eventually agreed—partly to get son to stop nagging, partly because house felt unbearable. Chose community with woodshop, close to golf course (Bob once loved golf but hadn’t played in years), strong men’s social group.

Results after 12 months:

- Physical health transformed—lost 25 pounds through regular meals and fitness classes, blood pressure and cholesterol improved dramatically, sleeping through the night again (insomnia resolved)

- Mental health recovery—depression lifted after 4 months of community engagement, grief counseling group in community helped process Linda’s death

- Resumed woodworking passion—makes furniture for grandchildren, teaches beginner woodworking classes to other residents, sense of purpose restored

- Surprised himself by becoming socially active—joined men’s group, plays poker weekly, volunteers driving other residents to medical appointments, started dating another resident (unexpected development)

- Relationship with son improved—son no longer worried constantly, visits quarterly (versus monthly “welfare checks”), conversations more genuine and positive

- Admits move saved his life—literally believes he’d be dead (suicide or neglect) if he’d stayed in house alone

“I moved here to shut my son up. I was miserable at first—missed Linda, missed our home, felt like I was in a prison for old people. But woodshop became my salvation. Then golf. Then the men’s group—bunch of guys who’d also lost wives and understood what I was going through without making it weird. Six months in, I realized I was laughing again. I’d forgotten what that felt like. Then I met Barbara—we’re just friends, but there’s a connection. I’m 79 years old and somehow I have a life again. If you’d told me a year ago I’d be happy in a retirement community, I’d have called you insane. But here I am. The house was killing me with memories and loneliness. This place gave me a reason to get up in the morning.” – Bob Sullivan

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I know when it’s the right time to move to senior housing?

There’s no single right answer—timing depends on individual circumstances. Consider senior housing when: home maintenance becomes burdensome or stressful rather than enjoyable, you’re socially isolated—days pass without meaningful interaction, minor health issues suggest future care needs likely (mobility challenges, chronic conditions), family worries constantly about your safety, you’re age 75-80 and healthy (optimal time for many—young enough to adjust, proactive before crisis). Warning signs you’ve waited too long: recent hospitalization or serious health event, living in unsafe conditions (cluttered home, expired food, poor hygiene), family members suggesting you need help (they often notice decline before you do), feeling overwhelmed by daily tasks. General principle: move while you’re healthy enough to fully participate in community life rather than waiting until crisis forces reactive decision. However, if you’re very happy at home, managing well, and socially connected, no need to rush. Regular reassessment (annually) helps catch gradual decline.

Can I afford senior housing on Social Security alone?

Difficult but sometimes possible depending on Social Security amount and community costs. Average Social Security: $1,907/month (2025). Independent living: $2,000-$4,500/month (typically exceeds Social Security alone). Assisted living: $4,500-$7,500/month (definitely exceeds Social Security). Strategies if Social Security is primary income: Choose low-cost geographic area—same quality community costs 40-60% less in smaller cities versus coastal metros. Consider subsidized senior housing—HUD Section 202 housing provides affordable apartments for low-income seniors 62+. Waiting lists long (1-2 years) but rents typically 30% of income. Some states offer subsidized assisted living for Medicaid-eligible seniors. Sell home to generate funds—even modest home provides $150,000-$300,000 supplementing Social Security for years. Home sale proceeds of $200,000 provides ~$1,600/month for 10 years (plus Social Security) making affordable senior housing possible. Use Veterans benefits if eligible—Aid & Attendance benefit adds $2,431/month to income. Apply for Medicaid—after spend-down, Medicaid covers some assisted living in participating communities. Reality check: Most Americans cannot afford quality senior housing on Social Security alone without home equity or other assets. Plan accordingly—save during working years, purchase long-term care insurance, or accept you may need family assistance or Medicaid eventually.

What’s the difference between independent living and assisted living, and how do I choose?

Key distinction: care services. Independent living provides housing, meals, activities, maintenance—but NO personal care assistance. You must be fully independent in all activities of daily living (bathing, dressing, toileting, eating, transferring, continence). Think of it as apartment building with amenities and social programming. Assisted living adds personal care assistance—staff help with bathing, dressing, medication management, etc. How to choose: Choose independent living if: fully capable of self-care, want maintenance-free living and social community, don’t need help with daily activities, looking to proactively downsize before care needs develop. Choose assisted living if: need help with one or more activities of daily living, require medication supervision, have mobility limitations needing assistance, doctor recommends supervised environment. Gray area: Some independent living communities offer “services packages”—you pay extra for specific assistance (medication reminders, extra housekeeping) without moving to full assisted living. Good option for minor needs. Financial consideration: Independent living costs 40-50% less than assisted living. Don’t choose assisted living prematurely just because “I might need it eventually”—you’re paying for care services whether you use them or not. But don’t stay in independent living if you’re struggling with daily activities and need assistance—that’s unsafe and defeats purpose of being in community.

Can I bring my pet to senior housing?

Depends on community—policies vary widely. Independent living: Most allow pets with restrictions—typically cats and dogs under certain weight limits (25-40 lbs common), some allow all sizes, may require pet deposit ($200-$500) and monthly pet fee ($25-$50), proof of vaccinations and licensing required. Assisted living and memory care: More restrictive—some allow small pets (under 20 lbs), many prohibit pets entirely citing safety concerns (tripping hazards, inability of residents to care for pets), some allow only caged pets (birds, fish). Important considerations when bringing pets: Can you physically care for pet (walking, feeding, grooming)? What happens to pet if your health declines and you can’t care for it? Does community have backup plan or will family take pet? Are there pet-friendly outdoor areas for walking dogs? Emotional benefit of pets for seniors is substantial—companionship, purpose, stress reduction. If pet is important to you, make pet policy a primary selection criterion. Visit community with your pet to see if environment feels appropriate. Alternative: Some communities have resident cats or visiting therapy animals providing pet interaction without ownership responsibility.

What happens if I run out of money while living in senior housing?

Difficult situation without easy answers. Scenarios depend on community type and contracts. CCRC with life care contract: If you qualified financially at entry and paid entry fee, community typically cannot evict you for inability to pay monthly fees. Contract guarantees care for life. However, you remain responsible for fees—community may put lien on estate or entry fee refund to recover unpaid amounts. Independent/assisted living without entry fees: If you can’t pay monthly fees, community can require you to leave after legal notice period (typically 30-90 days depending on state). They’ll work with you and family to find alternative placement, but ultimately can’t allow non-paying residents. Medicaid transition: Some assisted living facilities accept Medicaid after private-pay spend-down. If you qualify for Medicaid and facility has Medicaid beds available, you may transition to Medicaid payment. But many communities don’t accept Medicaid or limit Medicaid beds, so this isn’t guaranteed. Prevention strategies: Don’t commit to senior housing you can afford only by depleting all assets in 5-7 years without plan for later years, maintain emergency fund covering 24 months of fees, consider long-term care insurance before entering community, have frank discussion with family about financial backup plans, choose community that accepts Medicaid as safety net. Reality: Many middle-class seniors spend down assets paying for senior housing, then transition to Medicaid for nursing home care in final years. This is common and expected progression. Plan for it rather than hoping it won’t happen.

How do I involve my adult children in the decision without letting them take over?

Balance is tricky but achievable with clear communication. You want their input and support, but it’s your life and decision. Set boundaries upfront: “I value your opinion, but this is my decision. I’ll listen to your concerns, but I need you to respect my choice even if you disagree.” Make it clear you’re informing, not asking permission. Involve them constructively: Invite one or two adult children to tour communities with you—second opinion valuable and they’ll have better understanding of what you’re choosing. Ask them to research specific aspects (financial analysis, contract review, comparing communities) while you focus on lifestyle fit—divides labor productively. Have them talk to current residents and families during tours—they may ask different questions or notice different things. Request they attend meeting with financial advisor or attorney reviewing contracts—good to have family understand financial commitments. What NOT to do: Don’t let them narrow options before you see them—they may have different priorities than you. Don’t allow them to pressure you toward/away from specific communities based on their convenience (proximity to their homes) rather than your needs. Don’t sign contracts without your own independent review just because “the kids think it’s good.” Managing disagreement: If children oppose your choice, listen to specific concerns. Are they legitimate (financial unsustainability, care quality concerns) or emotional (they don’t want you to leave family home, they feel guilty)? If concerns are legitimate, address them. If emotional, acknowledge their feelings but maintain your autonomy: “I understand this is hard for you, but I’ve thought carefully and this is right for me.” Remember: They may be acting from love and concern, but they’re not living there—you are.

What if I choose a community and then hate it after moving in?

First, give it time—most seniors hate it initially but adjust within 3-6 months. Adjustment period is normal. Initial strong negative feelings don’t necessarily mean wrong choice. But if after 6 months you’re genuinely miserable, reassess. Check your contract: What’s the notice period required to leave? (typically 30-90 days). Is any portion of entry fee refundable? (varies widely—some communities refund pro-rated amount if you leave within first year, others non-refundable). Are there penalties for early departure? Before leaving: Identify specific problems—is it the community, or adjustment difficulty? Talk to community management about concerns—can anything be changed? Many problems are solvable. Consult with family and friends—outside perspective on whether concerns are legitimate or adjustment resistance. Try specific changes before leaving—different apartment if you don’t like yours, switching meal times or tables if social issues, giving specific activities more time. If you decide to leave: Give proper notice per contract, document condition of apartment (photos) to protect deposit refund, arrange alternative housing before leaving (don’t act impulsively without plan), understand financial implications—how much will you lose? Reality: Some people genuinely choose wrong community—personality doesn’t fit culture, location problematic, didn’t realize what community living would feel like. Better to acknowledge mistake and move than stay miserable for years. But ensure you’re not just resisting change—adjustment is hard, but most people who persist through initial difficulty ultimately glad they moved.

Are continuing care retirement communities (CCRCs) worth the high cost?

Depends on your specific situation, financial resources, and priorities. CCRCs are expensive—entry fees $100,000-$1,000,000+, monthly fees $2,000-$5,000+. For whom CCRCs make sense: Age 70-80, planning for long-term care needs, have assets for substantial entry fee plus reserves, want certainty—knowing you’ll never need to move again regardless of care needs, prioritize life care contract (locks in future care costs), value continuum of care on one campus, can afford to potentially “waste” money if you die early. For whom CCRCs don’t make sense: Limited assets—entry fee would consume majority of savings, prefer maintaining flexibility, uncomfortable with large upfront financial commitment, excellent health and unlikely to need assisted living or nursing care (may be paying for services you never use), want to leave substantial inheritance (entry fee significantly reduces estate). Financial break-even: With life care contract, you “break even” if you live long enough and need enough care. Example: $400,000 entry fee (90% refundable) + $4,000/month for 10 years = $880,000 total cost. If you eventually need 3 years assisted living ($7,000/month = $252,000) and 2 years nursing care ($10,000/month = $240,000), total would be $492,000 without CCRC. But with CCRC, all care included in monthly fee—saves $150,000+ in this scenario. But if you remain independent and die at 85, you spent $880,000 versus maybe $480,000 you’d have spent in independent living. Alternative strategy: Stay in own home or less expensive independent living. Use savings for assisted living/nursing home only if needed. May cost less overall if you die before needing extensive care or remain healthy long-term. Ultimately personal decision weighing financial resources, risk tolerance, and peace of mind value.

How do I evaluate the quality of food in senior housing?

Food quality dramatically impacts satisfaction—you’ll eat these meals daily for years. Critical to evaluate thoroughly. During tours: Eat multiple meals as guest—lunch AND dinner (quality sometimes differs). Try different meal options—don’t just get safest choice. Observe other residents’ plates—what are they eating? Do plates look appetizing? Talk to residents about food—”How’s the food here?” Most will answer honestly. Look at posted menus—variety over week? Repetitive? Dietary options (low-sodium, diabetic, vegetarian)? Observe dining atmosphere—rushed or relaxed? What to look for in good dining: Menu variety—different entrée options daily, rotating menu (not same meals every week), seasonal changes, special meals for holidays, ethnic food variety. Quality ingredients—fresh vegetables and fruits (not just canned), real proteins (not just processed), home-cooked appearance (not institutional). Dietary accommodations—staff know residents’ dietary restrictions, careful about cross-contamination for allergies, puréed options for swallowing difficulties, portion sizes for various appetites. Dining atmosphere—table service in some communities (servers take orders), pleasant environment (not hospital cafeteria feel), able to sit with friends, comfortable pace (not rushed). Flexibility—multiple meal times, ability to skip meals without penalty, snacks available between meals, room service for when you’re ill. Red flags: Majority of residents eating in apartments rather than dining room (suggests bad food), same menu repeating weekly, heavily processed institutional food, residents complaining about food (listen!), limited options (“take it or leave it” approach). Remember: Even good dining programs have occasional off days. Look for patterns, not single meal assessment.

What questions should I ask about the contract before signing?

Senior housing contracts are complex legal documents—read carefully and have attorney review before signing. Critical questions: “What is included in the monthly fee and what costs extra?” Get exhaustive list—ambiguity leads to surprise fees later. “How much have monthly fees increased each year for past 5 years?” Average percentage tells you future expectations. “Under what circumstances can you raise my monthly fees beyond standard annual increase?” Some contracts allow extraordinary increases if community faces financial challenges. “What happens to entry fee if I leave after 1 year? 5 years? 10 years? When I die?” Calculate various scenarios—is it refundable? When? To whom? “Under what conditions can you require me to leave the community?” Most contracts include clauses allowing eviction for non-payment, behavior disruptions, or care needs exceeding community capabilities. Understand specifics. “What happens if I can no longer afford the monthly fees?” Some CCRCs with life care contracts guarantee you can stay; others require you to leave. Critical distinction. “If care needs increase, how is that assessed and what are the associated costs?” Who determines care level? How often reassessed? Can you appeal care level determinations? “What happens if the community closes or declares bankruptcy?” Some contracts have guarantees; others leave you vulnerable. “Are there any liens or encumbrances on the property?” Financial due diligence—ensure community isn’t overleveraged. “Can I see your most recent audited financial statements?” Reputable communities provide this—if they refuse, red flag. Have attorney review: Don’t rely on community’s explanation of contract—they’re selling. Pay attorney $500-$1,000 to review before signing $100,000-$500,000+ commitment. Worth every penny.

Take Action: Your Housing Decision Roadmap

- Assess your current situation honestly this week – Create written inventory: Activities of daily living—can you manage bathing, dressing, toileting, eating, transferring, continence without help? Home maintenance—is yard work, repairs, cleaning becoming burdensome? Social isolation—how many meaningful conversations do you have weekly? Safety concerns—falls, medication management, driving worries? Health trajectory—are chronic conditions worsening? Financial situation—can you afford current home long-term? This honest assessment determines timing and housing type needed. Share assessment with family member or friend for objective perspective—we often minimize our struggles.

- Research 5-7 communities in your desired area within 2 weeks – Start online: Google “[your city] independent living” or “assisted living.” Visit seniorhousingnews.com, caring.com, aplaceformom.com for directories. Read reviews on Google and Senioradvisor.com—look for patterns, not single extreme review. Check state licensing websites for inspection reports on assisted living communities. Create spreadsheet comparing: housing type (independent, assisted, CCRC), base monthly cost, entry fees if applicable, location (proximity to family, medical), size (number of residents), online reviews summary, inspection report findings if assisted living. Schedule tours at 3-5 communities that seem promising. Don’t overwhelm yourself touring 10+ communities—after 5, they blur together.

- Tour top 3-5 communities over next 4-6 weeks – Schedule initial tours with all communities within 2-week period so you can compare while fresh in mind. During tours: Bring notebook and questions list, eat at least one meal at each, talk to residents without staff present (ask: “Would you choose this again?” “What surprised you?” “Any regrets?”), observe staff interactions with residents, take photos (if allowed) of apartments and common areas for later comparison. Return for unannounced visits to top 2-3 choices—different times of day, weekend if possible. Arrange overnight stay if community offers it—invaluable experience.

- Complete financial analysis before making decision – Calculate affordable monthly amount: retirement income minus other fixed expenses = housing budget. Compare to community costs with 4-5% annual increase assumption. Project costs for 10-15 years—can you afford it? Include all costs: entry fees, monthly fees, care level costs if assisted living, extra services likely to use, annual fee increases. Determine funding sources: home sale proceeds, retirement savings, long-term care insurance, Veterans benefits, other. Consult with financial advisor about: sustainable withdrawal rates from retirement accounts, tax implications of home sale, strategy for funding senior housing long-term, whether timing is financially optimal. Get pre-approval for entry if CCRC requiring financial qualifications—avoids disappointment after falling in love with community.

- Involve family in decision while maintaining your authority – Schedule family meeting or individual calls with adult children. Share your assessment, tour findings, and preliminary choice. Ask for their input: concerns about specific communities, questions you may not have considered, willingness to help with move, understanding of your financial situation and plans. Listen to concerns but be clear: “I value your opinion, but this is ultimately my decision. I need you to support my choice even if you’d choose differently.” If children want to tour communities, invite ONE to accompany you on follow-up visit—but you lead tours and ask questions. Their role is support and second opinion, not decision-making authority.

- Have attorney review contract before signing anything – Once you’ve selected community, request contract for review BEFORE committing any money. Take to elder law attorney (not general practice lawyer—specialized expertise matters). Attorney reviews: Entry fee refund terms and conditions, monthly fee structure and increase provisions, care level assessment and cost provisions, conditions under which you can be required to leave, what happens if you can’t afford fees, financial stability clauses, dispute resolution procedures. Attorney consultation: $500-$1,000 typically—worth it for $100,000-$500,000+ commitment. Don’t skip this step due to cost—expensive mistakes far exceed attorney fee. Attorney may negotiate changes or flag deal-breakers. Only after attorney approval and your complete understanding should you sign and submit deposit.

Disclaimer

This article is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute professional legal, financial, or medical advice. Senior housing decisions involve complex legal contracts, significant financial commitments, and personal health considerations that vary by individual circumstances. Laws, regulations, and community policies differ by state and locality. Costs, availability, and services described reflect general 2025 market conditions but vary widely by geographic location and specific community. Before making any senior housing decision, consult qualified professionals: elder law attorneys for contract review, financial advisors for funding strategies, physicians for health and care need assessments. Tour multiple communities personally and verify all information directly with communities rather than relying solely on this article. The author and publisher assume no liability for decisions made based on this information.

Information current as of October 2, 2025. Senior housing market conditions, costs, regulations, and availability subject to change.

Related Articles

- Simple Home Adjustments That Improve Comfort for Seniors

- 7 Critical Things Seniors Over 65 Must Know Before Downsizing

“`

You may also like:

Updated October 2025