Visual Art by Artani Paris | Pioneer in Luxury Brand Art since 2002

Downsizing from a spacious family home to a smaller apartment represents one of retirement’s most emotionally challenging transitions, yet 68% of Americans over 65 will make this move according to 2024 AARP research. The physical process of fitting a lifetime’s possessions into 800-1,200 square feet feels overwhelming, while the emotional weight of releasing family memories and accepting reduced space triggers grief and anxiety. However, strategic interior design transforms downsizing from loss into liberation—creating homes that feel spacious, organized, and distinctly yours despite smaller square footage. This guide provides ten practical design strategies specifically addressing senior downsizing challenges: making small spaces feel larger, organizing efficiently, maintaining accessibility, preserving cherished items while releasing clutter, and creating the comfort essential for mental wellbeing during major life transitions. These tested approaches help thousands of seniors annually turn cramped apartments into personalized sanctuaries supporting independent living.

Understanding the Psychology of Downsizing for Better Decision-Making

The emotional difficulty of downsizing stems from identity attachment to possessions and spaces. Your 3,000-square-foot house holds 40 years of accumulated belongings representing different life chapters—raising children, career success, hobbies pursued, travels taken. Each item connects to memories and identity: “I’m someone who entertains,” “I’m a collector,” “I’m prepared for anything.” Releasing possessions feels like releasing parts of yourself. A 2024 University of Michigan study found that seniors downsizing experienced grief symptoms comparable to losing a loved one, with depression and anxiety peaking during the first 3-6 months.

Reframe downsizing as intentional curation rather than deprivation. You’re not losing possessions—you’re choosing what matters most and releasing what no longer serves your current life. This shift from scarcity mindset (“I’m losing so much”) to abundance mindset (“I’m keeping my favorites and gaining freedom”) dramatically affects emotional experience. Research demonstrates that seniors who view downsizing as “editing to essentials” adjust 40% faster than those perceiving it as forced loss.

Recognize that smaller spaces require different living patterns. Large homes allowed spreading out—dedicated rooms for different activities, storage for “someday” items, space for rarely-used things. Apartments demand efficiency: furniture serving multiple purposes, belongings you actually use, thoughtful organization maximizing every inch. This isn’t compromise—it’s optimization. Many seniors report that after adjustment, they prefer apartment living’s simplicity to large house maintenance burdens.

Understand the grief process and give yourself permission to mourn. Leaving the family home where you raised children, hosted holidays, and built life triggers legitimate grief. Rushing through decisions or suppressing emotions leads to regret and depression. Allow 3-6 months for major downsizing decisions when possible. Visit your new apartment multiple times imagining daily life there. This realistic preview prevents unrealistic expectations causing post-move disappointment.

The financial reality often drives downsizing but creates additional stress. Selling a house while purging possessions while finding and furnishing an apartment overwhelms even organized people. Financial pressure (“I need to sell quickly”) conflicts with emotional need for gradual transition. If possible, separate timelines—downsize belongings before listing the house, or rent temporary storage during transition. This prevents desperate decisions you’ll regret when emotional dust settles.

Family dynamics complicate downsizing significantly. Adult children often push parents toward more drastic downsizing than necessary, motivated by concern or inheritance considerations. Conversely, some seniors resist needed downsizing from stubborn independence or denial about declining capabilities. Honest family discussions about practical needs, safety concerns, and emotional attachments prevent resentment. Including family in decisions doesn’t mean letting them control—you maintain final authority over your possessions and living arrangements.

Visual Art by Artani Paris

| Downsizing Stage | Common Emotions | Helpful Strategies | Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Phase | Anxiety, resistance, denial | Visit apartments, calculate costs, list pros/cons | 1-3 months |

| Sorting Possessions | Overwhelm, grief, guilt | Small daily sessions, “keep/maybe/go” system | 2-4 months |

| Letting Go | Loss, sadness, second-guessing | Photo documentation, thoughtful gifting to family | 1-2 months |

| Moving Day | Stress, exhaustion, nostalgia | Professional movers, family support, self-compassion | 1-3 days |

| Initial Adjustment | Disorientation, regret, loneliness | Unpack essentials first, establish routines | 2-4 weeks |

| Long-term Settling | Acceptance, relief, contentment | Personalize space, join community activities | 3-6 months |

Tip 1: Measure Everything Before Anything Else

The single biggest downsizing mistake is moving furniture that doesn’t fit, creating immediate stress and requiring expensive solutions. Before making any keep/donate decisions, obtain exact apartment measurements and create a scaled floor plan. This objective data prevents emotional decisions (“I love this sofa, I’m keeping it”) that create problems later when the beloved sofa overwhelms the living room making it unusable.

Visit your new apartment with a tape measure, notepad, and helper. Measure every room’s length and width, ceiling height, doorway widths, hallway widths, and closet dimensions. Note locations of electrical outlets, windows, and built-in features like radiators or air conditioning units. Photograph each room from multiple angles. These photos combined with measurements allow furniture planning from home without repeated apartment visits. Request a digital floor plan from the building management—many have these available.

Create a scaled floor plan using graph paper (1/4 inch = 1 foot) or free online tools like RoomSketcher or Floorplanner. Mark permanent features: windows, doors (showing swing direction), closets, outlets. Cut scaled templates of your existing furniture from graph paper or use software’s virtual furniture. This lets you test different arrangements before moving anything, revealing immediately what fits and what’s too large.

Measure pathways and clearances, not just wall-to-wall room dimensions. You need 36-48 inches of clear pathway for safe navigation, more if using walkers or wheelchairs. Doorways should accommodate furniture delivery—standard doorways are 30-32 inches, but measure yours. Hallways require turning clearance for moving furniture from room to room. That sofa fitting in the living room means nothing if it won’t navigate the hallway turn from the entrance.

Measure your current furniture precisely, including height, width, and depth. Large furniture that fits proportionally in spacious rooms overwhelms small apartments. A king bed appropriate for a 16×18 bedroom consumes a 10×12 apartment bedroom leaving no floor space. A 90-inch sectional sofa perfect for a 20×24 living room dominates a 12×14 apartment living room preventing other furniture or walking space. Be brutally honest about scale—smaller space requires smaller-scale furniture.

Calculate storage capacity in your new apartment versus current home. Walk-in closets in houses average 50-100 square feet; apartment closets average 4-8 square feet. Basements, attics, and garages provide hundreds of cubic feet of storage that apartments lack. Understanding this storage deficit guides possession decisions. If your apartment has 200 cubic feet of storage and you currently use 800 cubic feet, you must eliminate 75% of stored items or rent storage units (adding $100-200 monthly costs).

Prioritize rooms by usage when furniture won’t all fit. Most seniors spend 80% of home time in the living room and bedroom. These spaces deserve the most attention and best furniture. Dining rooms and guest bedrooms receive less priority—many successful downsizers eliminate formal dining (eating at kitchen counter or table) and guest rooms (guests stay in hotels or air mattresses in living rooms). Optimize for your daily life, not occasional guests.

Consider furniture arrangement options, not just fit. A room that technically fits three pieces might only have one workable arrangement, or maybe the only arrangement blocks outlets or windows. Test multiple layouts in your floor plan. If only one arrangement works and it’s awkward, that signals the need for different furniture. Flexibility in arrangement options indicates appropriate furniture sizing.

Measure vertical space and utilize height. Apartments often have 8-9 foot ceilings providing vertical storage opportunity. Tall bookcases, upper kitchen cabinets, over-door organizers, and wall-mounted shelves maximize space. Measure ceiling heights and window heights to ensure tall furniture fits and doesn’t block windows. Vertical thinking multiplies usable space when floor area is limited.

Document everything in a “measurement bible”—a three-ring binder or digital folder containing all measurements, photos, floor plans, and furniture dimensions. Reference this constantly during downsizing decisions. When questioning whether to keep furniture, consult your bible. Objective measurements prevent emotional decisions that create problems. Share this documentation with family members helping with decisions or moves—everyone works from the same factual information.

Tip 2: Use Multi-Functional Furniture to Maximize Space

Single-purpose furniture wastes precious apartment square footage. Every piece should serve multiple functions or provide hidden storage. This doesn’t mean sacrificing comfort or style—modern multi-functional furniture comes in attractive designs suitable for adult living spaces, not just college dorms. Strategic furniture choices can make an 800-square-foot apartment function like 1,200 square feet through intelligent design.

Ottoman coffee tables with hidden storage replace traditional coffee tables while providing seating and organization. Quality upholstered storage ottomans ($150-400) hold blankets, magazines, photo albums, or craft supplies while serving as foot rests, extra seating, or even TV trays with a top tray. Choose ottomans with sturdy, flat tops supporting drinks and lightweight items. This single piece replaces a coffee table plus separate storage furniture, saving 8-12 square feet.

Sofa beds or sleeper sofas accommodate overnight guests without dedicating an entire room to occasional visitors. Modern sleeper mechanisms have improved dramatically—memory foam mattresses and easy-opening frames make guest sleeping comfortable. Mid-range sleeper sofas ($800-1,500) provide daily seating and comfortable guest accommodation. This eliminates the need for a guest bedroom that sits empty 360 days yearly, freeing 100+ square feet for other uses.

Murphy beds (wall beds) fold up into cabinets when not in use, converting bedrooms into multi-purpose rooms. A bedroom with Murphy bed becomes office, craft room, or exercise space during daytime, then bedroom at night. Quality Murphy bed systems ($1,500-3,500 installed) include surrounding shelving and workspace. For seniors living alone in studio or one-bedroom apartments, Murphy beds in living areas create sleeping space while maintaining daytime openness.

Console tables that expand to dining tables provide everyday functionality plus entertaining capability. Narrow console tables (12-18 inches deep) fit against walls as sofa tables or entryway pieces, then extend to 30-36 inch depth seating 4-6 people. Prices range $300-800. This eliminates permanent dining tables dominating small living spaces while maintaining the ability to host family dinners. When not extended, the space serves as walkway or additional living area.

Lift-top coffee tables provide storage underneath plus elevated work surfaces for laptop use or meals from the sofa. The lift mechanism brings the table top up and forward, creating comfortable height for working or eating while seated. These tables ($200-500) typically include storage underneath for remotes, books, and electronics. This combination replaces traditional coffee tables plus TV trays plus side tables, consolidating three furniture pieces into one.

Nesting tables provide flexible side table options without permanent floor space commitment. Three nesting tables ($100-300) sit together as one unit normally, then separate when you need multiple surfaces for entertaining. The two smaller tables slide under the largest, occupying just 18×24 inches normally but providing three separate surfaces when needed. This flexibility proves particularly valuable in apartments where furniture arrangement changes based on activities.

Beds with built-in storage drawers eliminate the need for separate dressers. Platform beds with four to six large drawers ($400-1,200) store clothing, linens, or seasonal items underneath. This can eliminate one or two dressers, saving 8-16 square feet of bedroom floor space. Ensure drawer clearance—you need 30 inches of space in front of the bed to pull drawers fully open, so measure your bedroom before committing to this solution.

Bookcases with doors at bottom provide both display and hidden storage. Open shelves display books, photos, and decorative items, while closed cabinets below hide clutter, paperwork, or items you need but don’t want visible. These dual-purpose pieces ($250-600 for quality units) replace separate bookcases and storage cabinets, consolidating functions. Choose bookcases with adjustable shelves accommodating various item sizes as your needs change.

Avoid furniture that doesn’t earn its footprint. Decorative chairs nobody sits in, occasional tables holding nothing, display-only furniture serving no practical purpose—these waste space. Every furniture piece should pass the “use test”: you use it at least weekly, or it provides essential storage, or it serves a specific necessary function. Beautiful but useless furniture is a luxury large homes afford; apartments cannot.

Invest in quality multi-functional pieces rather than cheap single-purpose furniture. A $1,000 Murphy bed system providing bedroom and office space offers better value than a $400 regular bed plus a $400 desk that overcrowd a room. Multi-functional furniture costs more initially but delivers space efficiency impossible to achieve with multiple separate pieces. Calculate cost per function, not just absolute price—a sleeper sofa providing seating and guest bed for $1,200 costs $600 per function, better value than $600 sofa plus $600 guest bed.

Visual Art by Artani Paris

Tip 3: Master the Art of Vertical Storage

Americans typically use only 50% of available storage space because we think horizontally—floor-based furniture and low shelving. Apartments demand vertical thinking, utilizing wall space from floor to ceiling. This approach can double or triple effective storage without increasing square footage. The key is making high storage accessible and organized, not just cramming items on top shelves where they’re forgotten.

Install floor-to-ceiling bookcases or shelving units rather than standard 5-6 foot models. An 8-foot tall bookcase provides 60% more shelf space than a 5-foot model while occupying the same floor footprint. IKEA Billy bookcases (7 feet tall, $80-120) or custom built-ins maximize vertical storage affordably. Place frequently-used items at reachable heights (waist to eye level), less-used items higher, and decorative or archival items highest. Use a sturdy step stool for occasional high-shelf access.

Add upper kitchen cabinets if your apartment has unused wall space above standard cabinets. Many older apartments have soffits or dead space above cabinets that could accommodate additional storage. Installing one or two upper cabinets ($200-400 with installation) provides space for infrequently-used serving pieces, small appliances, or bulk supplies. If structural modifications aren’t allowed, add open shelving or hanging racks for items used less frequently.

Utilize doors with over-the-door organizers that don’t require installation. Bedroom doors hold shoe organizers storing shoes, accessories, craft supplies, or cleaning products ($15-30). Bathroom doors accommodate towel racks, robe hooks, or hanging organizers for toiletries ($20-40). Closet doors hold belts, scarves, ties, or small items ($10-25). These solutions add 5-10 cubic feet of storage per door without occupying floor or shelf space.

Install wall-mounted shelves in living areas, bedrooms, and bathrooms for items you use regularly but don’t need furniture to store. Floating shelves ($20-50 per shelf) hold books, plants, photos, or decorative items at various heights creating visual interest while providing function. In bathrooms, wall shelves above toilets utilize otherwise wasted space for toiletries and linens. In bedrooms, shelves beside or above the bed replace bulky nightstands.

Use furniture with vertical elements like tall dressers (5-6 drawers) instead of wide, low dressers. A 50-inch tall, 30-inch wide dresser provides the same storage as a 35-inch tall, 50-inch wide dresser while saving 20 inches of wall space—significant in small rooms. Similarly, tall narrow bookcases work better than short wide ones. When shopping, compare height-to-width ratios; prioritize vertical designs in space-limited apartments.

Implement closet organization systems that maximize vertical hanging space. Double hanging rods in closets double capacity—hang shorter items (shirts, folded pants, skirts) on upper and lower rods. Add shelf dividers creating separate cubby spaces for folded items, preventing toppling stacks. Install hooks inside closet doors or on side walls for bags, belts, or jackets. A well-organized small closet can hold as much as a poorly-organized walk-in closet.

Mount televisions on walls rather than using TV stands. Wall-mounted TVs ($50-150 for professional installation) free up 6-12 square feet occupied by TV stands while creating a cleaner aesthetic. The space under the TV can accommodate a slim console for media devices, or remain open improving perceived room size. Ensure walls can support the weight—drywall alone won’t suffice; mounting requires studs or appropriate anchors for masonry walls.

Add vertical dividers in cabinets and drawers organizing items standing upright rather than stacked. Sheet pan organizers ($15-25) store baking sheets, cutting boards, and serving platters vertically in cabinets, making everything visible and accessible without unpiling. Drawer dividers create slots for plates stored on edge, doubling capacity versus stacking. This principle works for files, magazines, and craft supplies too—vertical storage prevents the “dig through the pile” problem.

Create “zones” at different heights for different purposes. Eye-level (4-6 feet) holds daily-use items you access frequently. Upper zones (6-8 feet) store occasional-use items like holiday decorations or off-season clothing. Lower zones (floor-2 feet) hold heavy items or bulky storage bins. This purposeful height organization makes the system functional rather than creating “out of sight, out of mind” storage where items are forgotten.

Avoid overloading vertical storage creating dangerous toppling hazards. Anchor tall furniture to walls using furniture straps ($10-20 for two straps)—essential in earthquake-prone areas but wise everywhere. Don’t stack items unsecured on high shelves where they might fall. Use bins or boxes containing loose items rather than piling individual objects. The goal is maximizing space safely, not creating hazards defeating the purpose of independent living.

Tip 4: Choose Light Colors and Mirrors to Expand Visual Space

Color psychology and strategic mirror placement create illusions of spaciousness transforming cramped apartments into seemingly larger, airier spaces. This costs far less than moving to actual larger apartments ($50-300 for paint and mirrors versus $200-500 monthly rent increases) while delivering measurable perceptual benefits. Studies show light-colored rooms feel 15-30% larger than identically-sized dark rooms according to 2024 environmental psychology research.

Paint walls in light, neutral colors reflecting maximum light. Whites, soft beiges, light grays, and pale blues make ceilings appear higher and walls farther apart. Benjamin Moore White Dove, Sherwin Williams Accessible Beige, or Behr Swiss Coffee work beautifully in apartments. Avoid stark white which feels institutional; choose warm whites with slight cream or beige undertones creating warmth while maintaining lightness. One gallon ($35-50) covers 350-400 square feet; most apartments need 3-5 gallons for full repainting ($150-250 in materials).

Use the same color throughout open living areas creating visual continuity. When walls, ceilings, and adjacent rooms share colors, the eye travels uninterrupted creating perceived spaciousness. Contrasting colors between rooms fragment space making each area feel smaller and disconnected. If you want color variety, limit bold colors to small accent walls (one wall per room maximum) keeping the majority light and cohesive.

Position large mirrors opposite or adjacent to windows doubling natural light and creating depth illusions. A 30×40 inch mirror ($80-200) on the wall across from a window reflects the outdoor view, making the room feel like it has an additional window. Mirrors beside windows capture and distribute sunlight throughout the space. Avoid placing mirrors where they reflect clutter or less attractive views—strategic placement matters as much as size.

Create mirror gallery walls using multiple smaller mirrors instead of one large mirror. Grouping 5-9 decorative mirrors of various sizes ($15-40 each) creates visual interest while expanding perceived space. Arrange mirrors with 2-4 inches between frames for cohesive grouping. This approach costs less than single large mirrors while adding personality. Use mirrors with frames coordinating with your decor style—warm metallic frames for traditional spaces, simple frames for modern aesthetics.

Install mirrored closet doors if your apartment allows modifications. Bifold or sliding mirrored doors replace solid doors, instantly making bedrooms feel twice as large. These doors ($200-400 installed) provide full-length mirrors for dressing while visually expanding cramped bedrooms. If permanent installation isn’t permitted, lean oversized standing mirrors ($100-250) against walls—place felt pads underneath preventing floor scratches and wall contact preventing damage.

Choose furniture with light-colored upholstery and wood tones maintaining the airy feeling. Dark furniture visually weighs down small spaces, while light neutrals and natural woods keep rooms feeling open. Cream, taupe, light gray sofas and chairs with light oak, maple, or whitewashed wood pieces create continuity with light walls. You can add color through easily-changed accessories (pillows, throws) rather than permanent large furniture pieces.

Maximize natural light by keeping window treatments light and minimal. Sheer white or cream curtains provide privacy while allowing light penetration. Avoid heavy drapes or dark colors blocking windows. If privacy isn’t a concern, leave windows uncovered entirely—nothing expands space like abundant natural light. For windows requiring coverage, top-down/bottom-up shades or cellular shades in white allow flexible light control while maintaining brightness.

Add reflective or glass surfaces throughout the apartment bouncing light and creating openness. Glass or lucite coffee tables, metallic lamp bases, glossy ceramics, and glass-door cabinets contribute to overall lightness. Unlike solid wood or dark finishes absorbing light, reflective surfaces amplify available light making spaces feel larger and brighter. Balance is key—too much reflection becomes visually cold, so combine reflective elements with warm textiles and wood tones.

Keep walls relatively clear of heavy artwork or busy patterns that visually close in space. Large-scale, light-colored abstract art or simple landscape photography in light frames contributes to openness better than gallery walls of small dark pieces. If you love displaying many photos or artwork, dedicate one wall as a gallery wall while keeping other walls clear. This focused approach prevents the “covered walls” feeling that shrinks perceived room size.

Avoid the temptation to use only white throughout—this creates sterile, uncomfortable spaces. Layer shades of cream, beige, soft gray, and warm white for depth and interest while maintaining lightness. Add warmth through wood tones, warm metallics (brass, copper), and warm-toned textiles. The goal is bright and spacious, not cold and institutional. Think “Scandinavian” or “coastal” design rather than “hospital” or “rental white box.”

| Design Element | Space-Expanding Choice | Space-Shrinking Choice | Cost Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wall Color | Light neutrals (white, beige, soft gray) | Dark colors (navy, charcoal, burgundy) | Same cost |

| Furniture | Light upholstery, natural wood | Dark upholstery, dark wood | Same cost |

| Mirrors | Large, strategically placed | None or small decorative only | +$100-300 |

| Window Treatments | Sheer, white, minimal | Heavy drapes, dark colors | -$50-150 (simpler = cheaper) |

| Flooring | Light wood, light carpet | Dark wood, dark carpet | Same cost |

| Lighting | Multiple sources, bright bulbs | Single overhead, dim bulbs | +$100-200 |

Tip 5: Ruthlessly Curate Belongings Using the “One Year Rule”

The hardest part of downsizing isn’t arranging furniture—it’s deciding what possessions to keep versus release. Most seniors accumulated belongings across decades, much of it unused for years but laden with emotional significance or “just in case” justification. The one-year rule provides objective criteria cutting through emotional attachment: if you haven’t used, worn, or enjoyed an item in the past year, you won’t use it next year either. This rule eliminates 60-70% of possessions for typical downsizers, according to professional organizers.

Apply the one-year rule category by category, not room by room. Start with clothing—the easiest category emotionally and physically. Remove every item you didn’t wear in the past year (excluding special occasion items like funeral suits or wedding guest dresses). Be honest: clothes that didn’t fit, styles you felt uncomfortable in, items waiting for weight loss—these won’t get worn. Donate, sell, or give to family. Most people wear 20% of their clothes 80% of the time; downsizing forces identifying that active 20%.

Tackle kitchen items using frequency of use. Remove duplicate items keeping only the number you actually use. You don’t need 20 coffee mugs when you use the same two favorites daily. Keep one set of dishes for daily use, one nice set for holidays, and donate the rest. Specialty appliances used once yearly (bread makers, fondue pots, electric griddles) can be borrowed, rented, or simply skipped—the occasion isn’t worth the storage space they demand.

Address hobby and craft supplies realistically. That sewing machine unused for five years won’t suddenly become useful in a smaller space. Unfinished craft projects languishing for years won’t get completed—keep active projects only. Materials for hobbies you’ve moved on from serve no purpose except guilt. Donate usable supplies to senior centers, schools, or craft groups where they’ll actually get used. Focus storage on current, active interests rather than past or aspirational hobbies.

Books deserve special attention because many seniors have hundreds accumulated over lifetimes. Keep favorites you reread, reference books you consult regularly, and books with significant sentimental value (first editions, signed copies, family heirlooms). Release books you read once years ago and don’t remember, duplicates of classics available at any library, outdated reference books superseded by internet information. Aim to keep 20-30% of your collection—the books that truly matter to you now.

Paperwork and documents require ruthless culling. Keep only: current year tax documents plus seven prior years, active warranties and manuals, vital records (birth certificates, property deeds, wills), and active financial statements. Shred or recycle: old tax documents beyond seven years, expired warranties, manuals for items you no longer own, old greeting cards (photograph favorites first), magazine clippings you’ve never referenced. Most Americans keep 10x more paper than necessary.

Sentimental items create the greatest struggle. You can’t keep everything from your children’s childhoods, every gift received, every souvenir purchased. Choose 5-10 truly meaningful items per person or category, photograph the rest, then release. Your children’s artwork: keep their very best pieces, photograph others before recycling. Travel souvenirs: keep a few favorites evoking strong memories, release generic items. Inherited family items: keep pieces you actually love and use, pass others to family members who appreciate them more.

Apply the “does this serve my life now” test to everything uncertain. Past you might have needed that item, but does current you? Future you might theoretically need it, but realistically will you? If honest answer is no, release it. This principle eliminates “just in case” items that fill storage “in case” scenarios that never occur. Living in 800 square feet means prioritizing items serving your actual current life, not imagined future scenarios.

Create a “maybe” box for items you can’t decide about immediately. Pack uncertain items in a box, seal it, date it, and store it. If you haven’t needed anything from the box in six months, donate it unopened. This removes decision paralysis while providing security that you’re not being too hasty. Most people never open maybe boxes, realizing they didn’t need or miss those items. The few times you do need something, you can replace it if necessary.

Offer items to family before donating or discarding. Adult children or grandchildren might want family furniture, dishes, or heirlooms. Give them first choice, but don’t let guilt prevent donating items nobody wants. Many seniors keep things because “the kids might want this,” but when offered, kids decline—they have their own space limitations. Offer once, accept their decision gracefully, then release items without guilt. Your possessions are not their obligation.

Tip 6: Create Defined Zones in Open-Plan Living Spaces

Many modern apartments feature open-plan layouts combining living, dining, and kitchen areas in one space. Without defined zones, these areas feel chaotic and cluttered. Strategic furniture placement, area rugs, and lighting create distinct functional areas within open plans, making 600-square-foot spaces feel organized like 1,000-square-foot apartments with separate rooms. This zoning approach provides psychological benefits—clear zones reduce visual stress and help brains process spaces as organized rather than jumbled.

Use area rugs to define living, dining, and sleeping zones visually. A 5×7 or 8×10 rug under seating furniture anchors a living area. A 4×6 rug under a dining table defines eating space. In studio apartments, a rug under or beside the bed separates sleeping from living areas. Choose rugs in coordinating colors or patterns maintaining visual flow while providing distinction. Ensure rugs lay flat with non-slip pads—tripping hazards defeat the organizational purpose.

Position furniture creating implied walls or boundaries between zones. A sofa placed perpendicular to a wall (rather than against it) creates a room divider effect, with living space on one side and dining or sleeping on the other. A bookcase used as a room divider provides storage while separating zones. Console tables behind sofas define boundaries while adding surface space. These arrangements eliminate the “everything in one big room” feeling without requiring actual walls.

Install lighting specific to each zone rather than relying on single overhead fixtures. A living area needs floor lamps beside seating and perhaps a table lamp. A dining area benefits from pendant lights or a chandelier centered over the table. A bedroom zone requires bedside lamps. This layered, zone-specific lighting makes each area feel distinct and appropriately lit for its function. Different lighting levels also create visual separation between zones.

Use different wall colors or accent walls distinguishing zones in open plans. Paint the wall behind your bed a different color from living area walls, creating visual bedroom definition. An accent wall behind a dining table signals a separate eating zone. Keep colors coordinating—different tones of the same color family rather than wildly contrasting schemes. Too much color contrast fragments small spaces, while subtle shifts create distinction without chaos.

Add room dividers or screens creating flexible privacy and definition. Folding screens ($100-300), curtain dividers ($50-150 with ceiling track), or open shelving units ($150-400) separate sleeping from living areas in studios or large bedrooms converted to multi-use spaces. These dividers provide visual separation and some sound absorption without permanent construction. Choose dividers allowing light passage—solid walls shrink spaces while translucent or open dividers maintain openness.

Establish traffic patterns respecting zones you’ve created. Main walkways should go around defined zones, not through them. If you must walk through your living area zone to reach the kitchen, arrange furniture creating a clear pathway rather than forcing navigation around randomly-placed pieces. Think of zones as rooms—you wouldn’t walk through the middle of a traditional living room to reach another area; apply the same logic to open-plan arrangements.

Vary furniture heights creating visual interest while defining zones. Living areas might feature a low coffee table and low seating. Dining zones have higher tables and chairs. Work zones use desk-height surfaces. This height variation signals functional differences and creates visual rhythm preventing the monotonous “everything at the same height” problem. Varying heights also improves sightlines—you can see across a low living area to a higher dining area beyond.

Add plants or tall decorative elements marking zone boundaries. A large floor plant placed at the edge of a living area signals “this is the end of this zone.” A tall vase or sculpture on a console table behind a sofa reinforces the boundary. These natural markers create gentle division without harsh lines or bulky furniture. Plants particularly soften open spaces while providing health benefits and visual interest.

Maintain some visual connection between zones avoiding excessive separation. The goal is organized distinction, not total isolation making the space feel chopped-up. Use coordinating colors, similar styles, or repeated elements (same wood tones, matching metals) creating flow between zones. If your living area features warm beige and blue, incorporate those colors in dining and sleeping zones. This repetition unifies while allowing each zone its distinct character.

Resist the temptation to cram too many zones into limited space. A 400-square-foot studio realistically accommodates sleeping, living, dining, and possibly small work zones. Attempting to add craft zones, exercise zones, and guest zones creates overcrowded chaos. Prioritize essential zones, and accept that some functions happen in flexible ways (yoga mat in living zone, folded when not in use) rather than requiring dedicated permanent spaces.

Visual Art by Artani Paris

Tip 7: Prioritize Accessibility and Safety in Layout Decisions

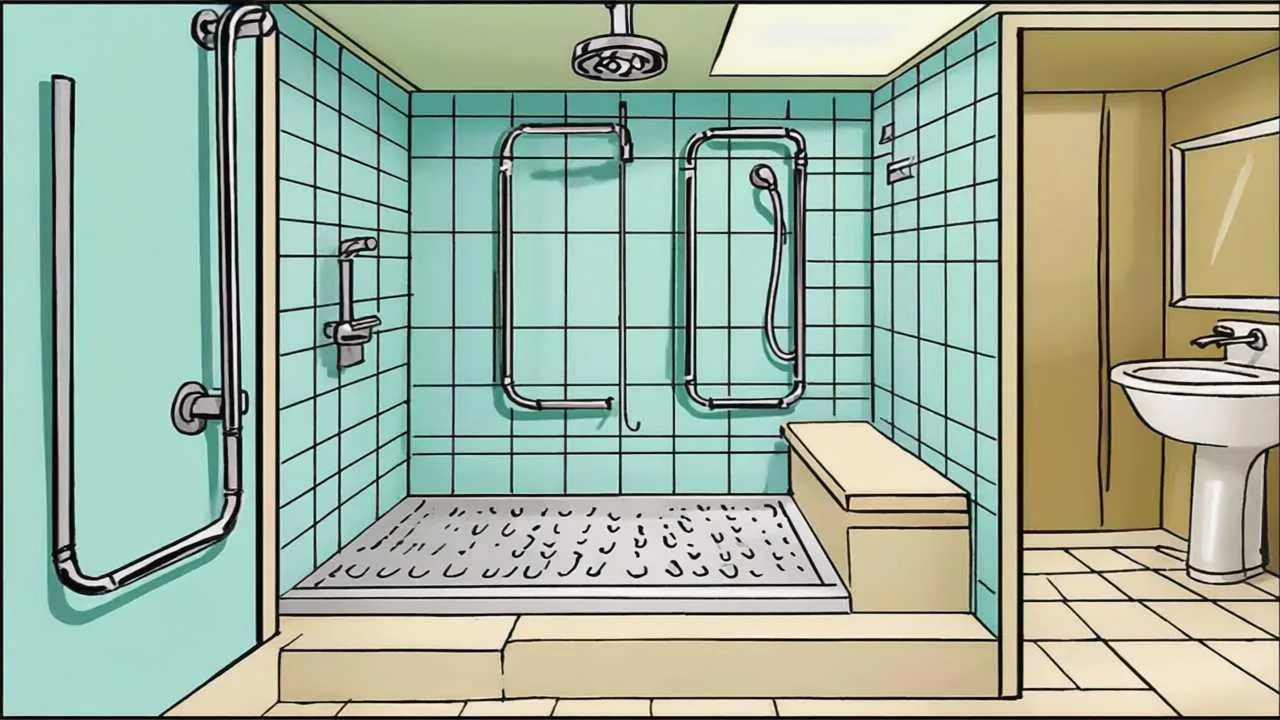

Downsizing often coincides with declining mobility, making accessibility planning essential during the move rather than afterthought modifications later. Furniture arrangement, storage placement, and pathway clearances directly affect your ability to age safely in place. Poor layouts cause falls, limit independence, and accelerate decline. Strategic accessibility planning costs nothing but prevents injuries potentially costing thousands in medical bills and rehabilitation. According to 2024 CDC data, 40% of senior falls occur in living rooms and bedrooms due to furniture placement and clutter.

Maintain 36-48 inch clear pathways throughout your apartment, measuring with a tape measure rather than estimating. Walker users need 48 inches minimum; wheelchair users need 5 feet for comfortable navigation. Main traffic routes—entrance to living area, living area to kitchen, bedroom to bathroom—require widest clearances. Secondary paths like approaching storage or less-used furniture can be narrower but never less than 36 inches. Mark desired pathways on your floor plan before placing any furniture.

Position frequently-used items at reachable heights (waist to shoulder level) eliminating excessive bending or stretching. Store everyday dishes in lower cabinets rather than upper. Keep commonly-worn clothes in middle dresser drawers, not bottom drawers requiring deep bending. Place remote controls, phones, and daily medications on surfaces at seated arm height. This “golden zone” storage (30-60 inches from floor) reduces physical strain and fall risks from excessive reaching or bending.

Eliminate tripping hazards including throw rugs without non-slip backing, electrical cords crossing pathways, low furniture difficult to see, and floor clutter. Secure all area rugs with proper non-slip pads or double-sided tape. Run cords along walls secured with clips or covers, never across walkways. Choose furniture in colors contrasting with flooring—dark furniture on dark floors creates trip risks from poor visibility. Implement the “clear floor” policy: nothing stored on floors except furniture.

Install adequate lighting especially in transition areas between rooms and zones. Falls spike at doorways, hallways, and stairs due to inadequate lighting during navigation transitions. Add nightlights along pathways from bedroom to bathroom, living room to kitchen, and entrance to living areas. Motion-sensor lights provide illumination automatically without fumbling for switches. Ensure light switches are located at room entrances, not requiring navigation through dark spaces to reach lighting controls.

Furniture should have rounded edges and stable bases preventing tipping. Avoid glass-top tables (shattering hazard), unstable tables prone to tipping if leaned on, and furniture with protruding corners at hip or shin height. Choose pieces with sturdy legs and broad bases. If you use furniture for balance support while walking, ensure it can bear your weight without sliding or tipping. Furniture doubling as mobility aids must be securely positioned and stable.

Create clear zones for assistive devices—walkers, wheelchairs, canes—when not in use. These devices become tripping hazards when left randomly around apartments. Designate spots near the entrance, beside your bed, and near seating where devices remain when you’re not using them. Wall-mounted cane holders ($15-25) or dedicated walker parking spaces keep devices accessible but organized. Never leave assistive devices in pathways or propped against furniture where they might fall.

Ensure bedroom layout allows emergency exit from both sides of the bed. If one side is against a wall, you’re trapped if you fall on the open side and can’t cross the bed. Position beds allowing access from both sides provides escape routes during emergencies and allows caregivers to assist from either side if needed. This might mean downsizing from a king to a queen bed to fit both-sides-accessible arrangement in smaller bedrooms.

Position seating allowing safe entry and exit without obstacles. Chairs and sofas need 24-30 inches of clear space in front for sitting and standing. Place seating near but not blocking pathways, so you can approach directly rather than squeezing between pieces. Ensure seating doesn’t face walls at very close distance—feeling trapped spatially increases anxiety and makes safe exiting difficult. Consider sight lines too—seating with clear view of entrance doors provides security awareness of visitors or emergencies.

Plan for future mobility changes even if current abilities are good. The “can I navigate this in a wheelchair” test prevents needing to rearrange everything when mobility declines. Doorways should stay clear, pathways should accommodate assistive devices, and high-traffic areas should have grab bar installation potential (solid walls, not just drywall). Forward-thinking planning prevents disruptive and expensive future modifications. Aging in place requires designing for 5-10 years ahead, not just today’s abilities.

Tip 8: Digitize Memories and Documents to Reduce Physical Storage

Physical photo albums, document boxes, and memorabilia collections consume enormous space in small apartments. Modern technology allows preserving these memories digitally, freeing physical space while actually improving accessibility and preservation. A box of photos sitting in a closet gets viewed rarely if ever; the same photos scanned to a computer or cloud storage become accessible anytime from your tablet or shared easily with family. Digitization projects take time but deliver lasting space and organizational benefits.

Photograph or scan family photos systematically, working through one album or box at a time. Smartphones take adequate photos of photos—just ensure good lighting and hold the camera parallel to avoid distortion. For higher quality, use a flatbed scanner ($80-150) scanning at 300-600 DPI. Photo scanning services ($0.25-0.75 per photo) offer professional quality if you have hundreds of photos and limited time or tech comfort. Organize digital photos by decade, event, or person, creating folders matching your organizational preferences.

Scan important documents creating digital backup while eliminating paper storage. Birth certificates, passports, property deeds, insurance policies, medical records, and tax documents can all be scanned to PDFs and stored on your computer plus external hard drive or cloud service for redundancy. Keep original vital records (birth certificates, legal documents) but eliminate copies and supporting paperwork that only needs to exist digitally. A filing cabinet holding 2,000 sheets of paper becomes a 1GB folder occupying zero physical space.

Convert VHS tapes, cassettes, and old media to digital formats before they degrade further. Services like Legacybox ($40-100 depending on quantity) convert videotapes, film reels, slides, and audio recordings to digital files. If you have dozens of tapes, this investment preserves irreplaceable memories while eliminating boxes of obsolete media no longer viewable without special equipment. Digital versions can be easily shared with family members who’d never borrow boxes of VHS tapes.

Use photo books for curated memory displays instead of keeping thousands of loose photos. Services like Shutterfly, Snapfish, or Chatbooks ($15-40 per book) let you design photo books from digital images. Create one book per decade, one per family member, or themed books (weddings, vacations, grandchildren). Display 3-5 photo books on a shelf occupying 12 inches of space instead of 10 boxes of photos occupying 15 cubic feet. The books are actually viewable and shareable, unlike boxes stored away forgotten.

Create digital “memory boxes” organized by person, event, or theme in cloud storage. Google Drive, Dropbox, or iCloud (first 5-15GB free) provide secure storage accessible from any device. Organize folders logically: “Family Photos > Smith Family > Grandchildren > Emma” creates hierarchical structure. Add text files with captions or stories accompanying photos. Share folder links with family members so everyone can access family history. This collaborative approach enriches memories beyond what physical photo boxes stored individually could achieve.

Back up digital files in multiple locations preventing loss. Keep files on your computer’s hard drive, an external hard drive ($50-100 for 1-2TB), and cloud storage. This three-location rule ensures that if one fails, two backups remain. External hard drives last 5-10 years; replace them periodically transferring files to new drives. Cloud services provide automatic backup reducing risk of human error forgetting to save files manually.

Release physical items after digitizing without guilt. Photographs exist to preserve memories, not be objects themselves. Once memories are preserved digitally, the physical photos have served their purpose. Keep a few special physical photos if desired—perhaps 20-30 favorites displayed or in one album. Release the rest knowing memories are safe and actually more accessible than when stuffed in boxes. Future generations will appreciate receiving USB drives or cloud links rather than inheriting boxes of deteriorating photos to sort themselves.

Consider gifting digitized collections to family during your lifetime. Share digital photo collections with adult children and siblings, allowing them to enjoy family history while you’re alive to provide context and stories. Many seniors find this sharing process deeply satisfying—connecting generations through preserved memories. Create shared cloud albums family members contribute to, building collaborative family archives. This transforms dusty boxes into living, growing family repositories.

Digitize hobby documents and reference materials too. Recipes clipped from magazines, instruction manuals, craft patterns, gardening notes—all can be photographed or scanned then organized digitally. A filing drawer of recipes becomes a digital folder easily searched. Digitized recipes can be enlarged on tablets for easier reading while cooking. Instruction manuals clutter drawers unnecessarily when most are available free online or scannable to PDFs.

Accept that some physical items hold value beyond their content and deserve keeping. Your grandmother’s handwritten recipe cards, your child’s artwork, love letters from your spouse—these possess physical and emotional significance beyond information content. Don’t digitize and discard everything. Keep a reasonable number of physical sentimental items in a dedicated memory box ($30-50 for attractive storage boxes). The goal is reduction to manageable levels, not elimination of all physical memory objects.

Tip 9: Invest in Quality Pieces You Love Rather Than Filling Space

Downsizing offers opportunity to curate your environment intentionally, surrounding yourself with objects you genuinely love rather than accumulation from decades of “good enough” purchases. Small spaces magnify both beauty and mediocrity—every item is visible and impactful. This principle argues for fewer, better possessions over many mediocre ones. One beautiful chair you love beats three cheap chairs filling space. This shift from quantity to quality transforms apartments into personal sanctuaries reflecting your taste and values.

Evaluate existing furniture honestly: do you love it, or do you keep it because it’s functional? Functional suffices in large homes where mediocre pieces fade into background. Small apartments showcase every piece—mediocrity becomes glaring. If you dislike your current sofa but kept it because “it works,” downsizing offers justification for replacement. Invest in one quality sofa you love ($1,200-2,500) rather than moving a disliked sofa and adding other furniture trying to compensate for its inadequacy.

Apply the “love it or lose it” test to decorative items. If you don’t actively enjoy looking at something, it’s consuming space without providing joy. Keep art you find beautiful, sculptures you appreciate, photos evoking positive emotions. Release items kept from obligation, gifts you never liked, trendy purchases regretted, or objects you stopped noticing years ago. Every object in view should earn its place through beauty, utility, or meaning—preferably all three.

Budget more for fewer pieces you’ll use daily rather than spreading money across many items. That $400 invested in an exceptional coffee table bringing daily pleasure delivers better value than four $100 mediocre items you tolerate. Quality furniture lasts decades—buying once for $1,500 beats replacing $500 furniture every 5 years. Calculate cost per year of ownership: a $1,200 chair lasting 15 years costs $80 annually; a $400 chair lasting 4 years costs $100 annually. Quality is economy.

Seek pieces with emotional resonance or personal significance. Furniture from your childhood home, art from meaningful travels, handcrafted items from local artisans—these objects tell your story and make your apartment distinctly yours. Generic mass-produced décor creates generic spaces. Personal, meaningful objects create home. One inherited table loaded with family history outweighs ten anonymous tables from big-box stores.

Choose classic, timeless styles over trendy items quickly dated. Quality furniture in traditional, transitional, or simple modern styles remains attractive for decades. Trendy items look outdated in 3-5 years, requiring replacement or living with embarrassingly dated spaces. At 70+, your furniture purchases may be your last—choose styles you’ll love at 80 and 90, not what’s Instagram-popular today. Classic doesn’t mean boring; it means enduring beauty surviving fashion cycles.

Resist the urge to immediately furnish your entire apartment. Live with essential pieces for 2-3 months understanding how you actually use the space before adding more. You might discover you don’t need everything you thought you did. Many downsizers report that half-furnished apartments feel more spacious and serene than they anticipated, leading to permanent minimalism. Add pieces only when genuine need or opportunity for perfect item arises, not from urgency to “finish” furnishing.

Seek quality secondhand rather than cheap new. Estate sales, consignment stores, and online marketplaces offer quality furniture at 40-70% below retail. A solid wood dresser from the 1960s ($200-400 used) outlasts and outperforms a particleboard dresser ($300 new) while possessing character modern pieces lack. Inspect used items for structural soundness, but don’t reject based solely on cosmetic issues easily remedied with cleaning or minor repair.

Curate decorative collections displaying only best examples. If you collected something for decades, keep your 10-20 favorite pieces and release the rest. A focused, high-quality collection displayed beautifully creates more impact than masses of items crowding shelves. Apply museum thinking—museums display 10% of holdings, storing the rest. Your apartment isn’t a storage facility; it’s a curated display of your life’s best treasures.

Remember that empty space has value. Rooms don’t need every surface covered, every corner filled. Breathing room makes beautiful pieces shine and creates peaceful environments. Japanese aesthetic principles emphasize negative space allowing eyes and minds to rest. In small apartments especially, restraint in quantity elevates quality of chosen pieces. The space around objects matters as much as the objects themselves.

Tip 10: Establish New Routines and Organizational Systems Immediately

Successfully downsizing requires new habits matching your reduced space. Systems that worked in 2,500 square feet fail in 800. Establishing organizational routines immediately prevents clutter creep that gradually overwhelms small apartments. The “one in, one out” principle, daily tidying, and ruthless mail management must become automatic habits. Without intentional systems, small spaces quickly become chaotic, undoing all downsizing work and creating constant stress.

Implement the “one in, one out” rule for all categories: when you acquire something new, remove something existing. Buy new shirt? Donate an old one. Receive a gift? Find something to release. This maintains equilibrium preventing accumulation that downsized spaces can’t accommodate. The discipline feels restrictive initially but becomes liberating—you evaluate all new acquisitions against existing possessions, reducing impulse purchases and thoughtless accumulation.

Create a daily 10-minute tidying routine, ideally before bed. Return everything to designated homes—dishes to kitchen, clothes to closet, magazines to basket, remotes to tray. This brief daily reset prevents gradual entropy that’s overwhelming to address weekly. In small spaces, disorder multiplies visually because everything is visible. Daily attention maintains order; weekly attention allows chaos to accumulate beyond easy recovery.

Establish “homes” for every category immediately upon moving in. Mail goes in one designated spot, keys on one hook, medications in one drawer. When everything has a specific home, tidying is mechanical, not decision-making. Label shelves or drawers during initial setup if helpful. The first month’s habits persist indefinitely—good habits make life easy, bad habits create ongoing frustration.

Manage incoming mail ruthlessly using the “touch it once” principle. Sort mail immediately: trash/recycle (60-70%), pay/respond (20-25%), file (10-15%). Never set mail down to “deal with later”—this creates piles that grow exponentially. Shred/recycle junk mail immediately. Set up online billing eliminating most paper mail. Unsubscribe from catalogs. Most seniors can reduce mail by 80% through aggressive pruning of mailing lists.

Implement seasonal clothing rotation if closet space is limited. Store off-season clothes in under-bed storage, upper closet shelves, or hall closet. Keep current season clothes in the main closet. This doubles effective closet capacity by ensuring displayed clothes are actually wearable now. Mark calendar for seasonal switches (May 1 and November 1) making it automatic rather than something perpetually postponed.

Schedule monthly mini-purges addressing accumulation before it becomes overwhelming. Set a recurring calendar reminder: first Saturday monthly, review one category (books, kitchenware, bathroom supplies, decorative items). Remove items you haven’t used since the last review. This ongoing maintenance prevents needing major periodic purges. Small regular attention maintains order; neglect allows chaos requiring disruptive intervention.

Establish “holding zones” for items exiting your apartment. Keep a donation box or bag in your closet. When you identify items to release, place them immediately in the donation container. When full, drop at donation center—don’t let full boxes sit for weeks. Some seniors schedule monthly donation center trips, ensuring regular outflow matching any inflow. Friction in the removal process causes abandoned donation piles that become clutter themselves.

Create efficient morning and evening routines utilizing your space optimally. Knowing exactly where everything is and having systems for daily tasks reduces cognitive load and time wasted searching. Morning routine: clothes laid out previous night, breakfast items in same location, keys/wallet/phone in designated spot. Evening routine: dishes cleaned immediately, clothes put away, next day’s items prepared. Routines create efficiency making small-space living smooth rather than cramped.

Review systems quarterly, adjusting what isn’t working. If mail still piles, modify your system. If clothes overflow the closet, reassess what you’re keeping. If surfaces accumulate clutter, investigate why things aren’t returning to homes. Systems serve you—when they fail, change them rather than blame yourself. Flexibility in methods while maintaining overall principles of organization allows evolution matching your needs and capabilities as they change.

Real Transformations: Seniors Who Successfully Downsized

Case Study 1: From 2,400 to 850 Square Feet – Minneapolis, Minnesota

Eleanor and Frank Morrison (76 and 78 years old) leaving family home after 48 years

The Morrisons raised four children in their Minneapolis house, accumulating possessions from five decades. When Frank’s mobility declined after a stroke, maintaining the house and navigating stairs became impossible. They resisted downsizing for two years from emotional attachment and overwhelming logistics. Finally, their daughter hired a senior move manager ($1,200 for full service) who guided them through a 6-month downsizing process in early 2025.

They systematically addressed each room using the one-year rule. The move manager helped photograph family items offered to children, arranged estate sale for unwanted furniture ($2,800 earned), and coordinated movers. They kept: one small sofa (sold 3-piece sectional), lift chair, queen bed (from king), one dresser each (from three), and carefully curated decorative items. The 850-square-foot apartment felt spacious with proper furniture scaling. They installed floor-to-ceiling shelving for books and added mirrors expanding perceived space.

Results:

- Reduced monthly housing costs by $1,400 (mortgage + maintenance vs. apartment rent)

- Eleanor reported feeling “lighter” emotionally—relieved from stuff management burden

- Frank’s mobility improved with accessible, single-floor layout and grab bars

- After six-month adjustment, both reported preferring apartment living: “We should have done this sooner”

“I thought leaving our house would break my heart. Instead, I felt liberated. The stuff we accumulated over 48 years had become a burden, not a treasure. Our apartment has everything we need, nothing we don’t. We spend time living instead of maintaining a house and managing possessions.” – Eleanor Morrison

Case Study 2: Solo Downsize on Fixed Income – Tucson, Arizona

Carmen Ramirez (72 years old) widowed, living on Social Security

Carmen’s husband died in 2023, leaving her with a 1,800-square-foot house she couldn’t afford or maintain alone. Social Security provided $1,700 monthly—barely covering the mortgage. She needed to downsize to a $900/month apartment but had limited savings for moving costs. She tackled downsizing herself over eight months in 2024-2025, selling furniture through Facebook Marketplace ($1,400 earned) and Craigslist, donating extensively to local charities, and asking church friends for moving help.

Carmen’s biggest challenge was releasing her husband’s belongings—his workshop, clothes, collections. A grief counselor helped her understand that keeping possessions wouldn’t keep memories alive. She photographed everything, kept a few meaningful items, and donated the rest to veterans’ organizations her husband had supported. For her 650-square-foot apartment, she kept only furniture that fit the measured floor plan. She painted one wall terracotta, added smart lighting ($150), and positioned mirrors strategically.

Results:

- Reduced monthly costs by $1,200 (house expenses vs. apartment rent + utilities)

- Total moving costs: $800 (paint, small truck rental, helpers’ lunch, supplies)—covered by furniture sales

- Carmen created a cozy, personal space reflecting her taste rather than maintaining “our” house frozen in time

- Joined apartment complex’s social activities—made new friends reducing widow isolation

“I was terrified of downsizing alone on my limited budget. Taking it slow, selling things myself, and accepting help made it possible. My apartment isn’t as big as my house, but it’s mine. I can afford it comfortably, and it’s actually easier to keep clean and warm. I wish I hadn’t waited so long out of fear.” – Carmen Ramirez

Case Study 3: Pre-emptive Downsizing While Still Healthy – Portland, Oregon

Michael and Susan Chen (68 and 67 years old) planned downsizing before crisis

Unlike many seniors downsizing from necessity, the Chens proactively downsized while healthy and active in early 2025. They observed friends struggling with crisis-driven moves after health emergencies and decided to downsize on their terms while able to manage the process thoughtfully. They sold their 2,600-square-foot house and moved to a 1,100-square-foot condo in a walkable urban neighborhood they loved but couldn’t afford when raising children.

They took 10 months systematically downsizing, applying ruthless curation. They asked: “Does this serve our life now or our life five years ago?” Released: duplicate kitchenware, excess furniture, professional wardrobes (they’re retired), hobby equipment from abandoned interests, books they’d never reread. Kept: favorites from each category, travel souvenirs with strong memories, art they loved, and enough entertaining items for family gatherings. They invested in quality replacements scaled for the condo—beautiful sofa, lift chairs, perfect-sized dining table.

Results:

- House sale profit plus reduced housing costs funded travel and hobbies previously unaffordable

- Walkable location eliminated car dependency—Susan stopped driving due to vision changes without life disruption

- Maintenance-free condo living freed 10-15 hours weekly previously spent on house upkeep

- Both reported increased life satisfaction: “We designed our retirement lifestyle instead of defaulting to old patterns”

“Downsizing before we had to was the smartest decision of our retirement. We controlled every aspect rather than making desperate decisions during a health crisis. We live in a neighborhood we love, in a beautiful space we chose carefully, with only possessions that matter. Our friends say we’re brave, but it’s not bravery—it’s intentional living.” – Susan Chen

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does downsizing typically take from start to finish?

Timeline varies based on starting point and urgency. Planned downsizing averages 6-10 months: 2-4 months sorting and purging, 1-2 months finding an apartment, 1-2 months selling/donating, 2-3 months transition. Crisis-driven downsizing compresses this to 1-3 months causing significantly more stress. Allow longer if possible—rushing leads to regretted decisions and incomplete purging that continues plaguing you. If you have 6+ months, use them. The psychological benefits of gradual transition outweigh urgency’s temporary efficiency.

Should I downsize before or after selling my house?

Ideally, downsize possessions before listing your house for sale. Decluttered homes show better, photograph better, and sell faster at higher prices. Real estate agents report that staged, minimalist homes sell 30% faster than cluttered homes. Start purging 3-4 months before listing, intensifying as sale approaches. If you must sell quickly, consider temporary storage ($100-200 monthly) for excess items while downsizing post-sale. However, this adds stress and cost—better to declutter first when possible. Never move items you’ll immediately discard—purge before moving to reduce moving costs.

What do I do with items my adult children don’t want but I feel guilty discarding?

First, truly offer items with clear deadline: “I’m downsizing by March. Please take anything you want by February 15th.” After the deadline, guilt-free donation or sale is appropriate. Your children’s possessions are not your obligation beyond reasonable offering. Many seniors keep items “for the kids” that kids explicitly rejected—this serves neither party. Photograph items before donating so children can request copies if regret arises (rarely happens). Remember: burdening children with unwanted inheritance later is worse than donating now. Release guilt—you raised them, provided for them, and offered items. Your job is complete.

How do I handle the emotional grief of leaving my family home?

Recognize grief as legitimate and necessary rather than weakness to suppress. Allow yourself to mourn. Take photos or videos of every room before leaving. Write memories associated with spaces. Create a memory book combining photos and stories. Have a closing ritual—final walk-through alone or with family, saying goodbye to rooms and memories. Consider short-term counseling if grief feels overwhelming—many seniors benefit from 4-6 therapy sessions during major transitions. Join senior support groups where others share similar experiences. Understand that grief lessens with time—most seniors report that after 6 months in new apartments, attachment to old houses fades replaced by appreciation for current homes.

Can I successfully downsize if I’m not naturally organized or good at making decisions?

Yes, but consider hiring help. Senior move managers ($1,000-3,000 depending on scope), professional organizers ($50-100/hour), or even organized family members or friends can guide the process. These helpers provide objective opinions, make decisions when you’re paralyzed, and maintain momentum when you feel overwhelmed. The cost is investment in mental health and successful outcome. Alternatively, use structured decision frameworks: one-year rule, keep/maybe/go boxes, photograph-then-release for sentimental items. Systems compensate for natural disorganization. Many naturally disorganized seniors successfully downsize using external structure and help.

What’s the biggest mistake seniors make when downsizing?

Moving too much furniture that doesn’t fit, creating immediate regret and expensive problems. Measure everything first—apartment dimensions and all furniture. Create scaled floor plans testing arrangements. Be ruthlessly honest about scale—furniture perfect for 18×20 rooms overwhelms 12×14 apartments. Second biggest mistake: not purging enough initially, then struggling with cramped apartments requiring second-round purging that’s more stressful than doing it right initially. Third mistake: rushing the process making desperate decisions later regretted. Start early, measure accurately, purge thoroughly. These prevent most common downsizing disasters.

How do I know if I’m downsizing too much versus not enough?

“Too much” feels barren, uncomfortable, and lacking necessary items. “Not enough” feels cramped, cluttered, and difficult to navigate. Test by living with reduced items before final decisions. Create a “maybe” box for uncertain items—if you haven’t needed them in 6 months, you downsized appropriately. Most seniors err toward keeping too much rather than too little. If your new apartment feels crowded after move-in, continue purging. If it feels empty, you can add. Start conservative (less is more) and add back if truly needed. Furniture and items are replaceable; storage space is not.

Should I rent storage for items I can’t decide about immediately?

Storage units make sense for true short-term transitions (3-6 months) while settling into apartments and finalizing decisions. Long-term storage ($100-200 monthly) quickly becomes expensive—$1,200-2,400 annually storing items worth less than rental costs. Many seniors rent storage “temporarily” that becomes permanent, paying thousands storing forgotten items. If considering storage, set a firm 6-month deadline for retrieval or donation. Better approach: use “maybe” boxes in your apartment—if you haven’t retrieved items in 6 months, donate unopened. This costs nothing and forces honest evaluation of actual need.

How do I maintain my identity and sense of home in a smaller space?

Display curated items reflecting your life, interests, and values rather than generic décor. Keep your 20-30 favorite photos rather than all 500. Display the 10 travel souvenirs evoking strongest memories. Hang artwork you love. Use furniture you find beautiful. Smaller space doesn’t mean less personality—it means more intentional expression. Create one “memory wall” or shelf showcasing life’s highlights. Use colors you love. Maintain hobbies important to you even if space is limited. Identity comes from chosen, meaningful objects, not quantity of possessions. Many seniors report feeling more “themselves” in curated apartments than in cluttered houses where meaningful items got lost among masses of stuff.

What if I downsize and then regret giving away specific items?

Genuine regret is actually rare—most fears about regret exceed actual experience. Research shows only 5-10% of downsizers truly regret specific donation decisions. Photograph everything before releasing it—photos preserve memories and appearance. Keep a “released items” notebook listing what went where and why—this reduces anxiety about future regret by documenting thoughtful decisions. If you do regret something, assess if it’s genuine need or nostalgia. Can the item be replaced if truly necessary? Often yes, affordably. Can you borrow from family/friends if occasionally needed? Usually yes. The relief from living uncluttered vastly outweighs rare regret about specific items.

Is it better to downsize gradually or all at once in intensive effort?

Gradual downsizing (6-10 months) causes less emotional and physical stress, allows thoughtful decisions, and provides adjustment time. Work through categories systematically—clothes one month, kitchen next month, books following month. This steady approach prevents burnout and desperation decisions. Intensive downsizing (1-3 months) suits those with urgent timelines but creates overwhelm and regret. However, even within urgency, work systematically rather than randomly. If forced to intensive timeline, hire help—professional organizers, move managers, or dedicated family members. Regardless of pace, systematic approach beats chaotic rushing. Gradual when possible; intensive with help when necessary.

Action Plan: Your 10-Step Downsizing Roadmap

- Measure your new apartment precisely and create a scaled floor plan – Before making any decisions, obtain exact dimensions of every room, doorway, hallway, and closet. Draw a floor plan using graph paper or free software like RoomSketcher. Measure your current furniture. Test arrangements virtually before moving anything. This objective data prevents emotional decisions creating practical problems. Spend 2-3 hours on this foundational step—it guides every subsequent decision.

- Establish your timeline and work backwards to create schedule – If moving in 6 months, allocate: Month 1-2 for sorting and initial purging, Month 3 for major furniture decisions, Month 4 for selling/donating, Month 5 for final purging and packing, Month 6 for moving. Break large tasks into weekly mini-goals. Write deadlines on a calendar. Share timeline with family helping you. Accountability prevents perpetual postponement. Adjust timeline if urgent but maintain systematic approach even if compressed.

- Apply the one-year rule systematically to every category – Start with easiest category emotionally (usually clothing) building confidence for harder categories (sentimental items, collections). If you haven’t used, worn, or enjoyed something in 12 months, you won’t use it next year. Be ruthlessly honest. Create three piles: keep, donate, undecided. Place “undecided” items in dated boxes—if unused in 6 months, donate unopened. Work through one category weekly: Week 1 clothing, Week 2 kitchen, Week 3 books, Week 4 hobby items, Week 5 decorative items, Week 6 furniture decisions.

- Offer family items to relatives with clear deadlines – Email or call family members: “I’m downsizing and offering items you might want. Please respond by [date 4 weeks out] with what you’d like. Anything not claimed will be donated.” Include photos of available items. Set firm pickup deadline. After deadline, guilt-free donation proceeds. Don’t let “maybe someone wants this” prevent releasing items. Family has had opportunity; your responsibility ends there. This prevents storing items indefinitely hoping someone eventually wants them.

- Sell valuable items but donate everything else without guilt – Selling takes significant time and energy. Determine what’s worth this effort—antiques, jewelry, quality furniture might justify selling. Everything else should be donated immediately rather than languishing while you “plan to sell it.” The opportunity cost of your time and the storage space occupied often exceeds potential sale proceeds. Use Facebook Marketplace or Craigslist for valuable items ($100+). Donate the rest to Goodwill, Salvation Army, or charities providing free pickup. Release quickly rather than perfect monetization.

- Choose multi-functional furniture scaled appropriately for your space – Every furniture piece should serve 2-3 purposes or provide hidden storage. Replace oversized pieces with properly-scaled alternatives—queen bed instead of king, loveseat instead of sofa, console table that expands for dining. Invest in quality multi-functional pieces ($800-1,500 per major item) rather than cheap single-purpose furniture. Sofa with storage, ottoman serving as coffee table and seating, bed with drawers underneath—these choices maximize limited space effectively.

- Implement vertical storage solutions throughout your apartment – Install floor-to-ceiling shelving, add upper cabinets where possible, use over-door organizers, mount TVs on walls, choose tall narrow furniture over short wide pieces. Think upward, not outward. This approach doubles or triples effective storage without consuming additional floor space. Invest $200-500 in shelving, organizers, and mounting hardware. Ensure high storage remains accessible with a sturdy step stool. Organize vertically by frequency of use—eye level for daily items, upper areas for occasional use.

- Paint walls light colors and position mirrors strategically – Light, warm neutrals (soft white, beige, warm gray) make apartments feel 20-30% larger than dark colors. Paint main living areas including bedroom in cohesive light palette ($150-300 for paint and supplies). Position large mirrors ($80-200 each) opposite or adjacent to windows reflecting light and views. Create mirror groupings on empty walls. This visual expansion costs far less than moving to actual larger spaces while delivering significant perceptual benefits.

- Digitize photos, documents, and memorabilia freeing physical space – Scan or photograph family photos, important documents, and memorabilia preserving memories digitally (free using smartphone, $100-300 for scanning service if preferred). Store digital files on computer, external hard drive ($50-100), and cloud service (first 5-15GB free). Create digital photo books ($20-40 each) with curated favorites. Release physical items after digitization—memories are preserved and more accessible than boxes stored away. This single project can eliminate 10-20 cubic feet of stored materials.

- Establish organizational systems and daily routines immediately – Upon moving in, designate homes for every category before unpacking completely. Implement “one in, one out” rule, daily 10-minute tidying, and ruthless mail management from day one. First month’s habits persist indefinitely—establishing good systems early prevents clutter creep that gradually overwhelms small spaces. Write down your systems (where things go, daily routines, weekly maintenance tasks) and post somewhere visible until habits form automatically (usually 6-8 weeks). Systems maintain the hard-won organization achieved through downsizing.

Disclaimer

This article provides general interior design and downsizing guidance for seniors and does not constitute professional organizing services, real estate advice, legal counsel, or moving services. Individual circumstances vary significantly including physical capabilities, financial resources, family situations, and emotional readiness for downsizing. Consult with professional organizers, senior move managers, real estate agents, or financial advisors for personalized guidance. The timeline and cost estimates provided represent averages and may not reflect your specific situation. Always verify furniture dimensions, apartment regulations, and lease terms before making modifications or purchases.

Information current as of October 2, 2025. Moving and downsizing best practices continue evolving.

Related Articles

- Affordable Interior Upgrades for Seniors over 60 2025

- 10 Best Senior Friendly Home Interior Ideas for 2025

You may also like:

Updated October 2025