Visual Art by Artani Paris | Pioneer in Luxury Brand Art since 2002

Establishing a balanced daily routine becomes increasingly important in retirement years, providing structure that promotes physical health, mental sharpness, emotional wellbeing, and social connection while preventing the aimlessness and isolation that can lead to depression and cognitive decline. Research from the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry shows seniors with structured daily routines report 42% higher life satisfaction scores and 35% lower rates of depression compared to those without regular schedules. A well-designed routine balances essential activities—physical exercise, mental stimulation, social interaction, rest, and personal interests—creating days filled with purpose and accomplishment rather than emptiness and boredom. This comprehensive guide provides practical strategies for designing personalized daily routines that accommodate individual health conditions, energy levels, and interests while maintaining the flexibility needed for doctor appointments, family visits, and spontaneous opportunities that make retirement fulfilling rather than rigidly scheduled.

Why Daily Routines Matter for Senior Health and Wellbeing

The transition from structured work life to open-ended retirement often leaves seniors adrift without the external framework that previously organized their days. While retirement freedom is wonderful, complete lack of structure frequently leads to problematic patterns—staying up too late watching television, skipping meals, avoiding social interaction, neglecting exercise, and spending excessive time in pajamas scrolling through phones. These seemingly harmless habits compound over time, contributing to poor sleep, social isolation, physical decline, and depression.

Scientific research validates the importance of daily routines for older adults. A 2018 Northwestern University study tracking 1,800 seniors over five years found those with consistent daily routines showed 31% slower cognitive decline compared to peers with irregular schedules. The researchers concluded that predictable routines reduce cognitive load—your brain doesn’t constantly decide what to do next, preserving mental energy for more demanding tasks. Routine activities become automatic, freeing cognitive resources for learning, problem-solving, and social interaction.

Physical health benefits from routine are equally compelling. Regular meal times regulate blood sugar and metabolism, particularly important for seniors with diabetes or pre-diabetes. Consistent sleep schedules improve sleep quality—going to bed and waking at the same times daily strengthens your circadian rhythm, the internal biological clock regulating sleep-wake cycles. A 2020 University of Pennsylvania study found seniors with regular bedtimes (within 30 minutes nightly) slept 52 minutes longer on average and reported 48% better sleep quality than those with irregular schedules.

Emotional stability increases with routine predictability. Knowing what to expect reduces anxiety and provides comfort, particularly for those experiencing age-related changes or health concerns. Routines create a sense of control and competence—you know what you’ll do and when, building confidence through daily accomplishments. Completing routine tasks, even simple ones like making your bed or watering plants, provides satisfaction and purpose often missing in unstructured days.

Social connection benefits from scheduled activities. When you commit to Tuesday morning coffee with friends or Thursday afternoon book club, you maintain relationships that might otherwise fade through neglect. Routine social commitments combat isolation by creating regular human contact regardless of how you feel on particular days. On low-motivation days, scheduled commitments get you out the door when you’d otherwise stay home alone.

Mental health professionals increasingly recognize routine’s protective effects against depression. Depression thrives in unstructured time—when you have nothing specific to do, rumination and negative thinking fill the void. Structured days with varied activities interrupt negative thought patterns and provide external focus. A 2019 study in the Journal of Affective Disorders found seniors with structured daily routines showed 44% lower depression rates than peers without regular schedules, even after controlling for baseline health and social factors.

Creating an Energizing Morning Routine

Morning routines set the tone for entire days, making this period crucial for establishing positive momentum. The key is creating a sequence of activities that awakens your body and mind gently while providing structure and accomplishment before noon.

Wake-Up Time: Consistency Over Earliness

Contrary to popular wisdom, you don’t need to wake at 5 AM for a productive routine—consistency matters far more than specific time. Choose a wake-up time matching your natural chronotype (whether you’re a morning person or night owl) and health needs, then maintain it within 30 minutes daily, including weekends. Most seniors find 6:30-8:00 AM works well, allowing adequate sleep (7-8 hours nightly for most adults) while leaving full days ahead.

Avoid hitting snooze—this fragments sleep and makes waking harder. Set your alarm across the room, forcing you to physically get up to turn it off. Once standing, resist the temptation to return to bed. Open curtains immediately upon waking—natural light exposure signals your brain to stop producing melatonin (the sleep hormone) and start producing cortisol (which increases alertness), facilitating the wake-up process.

Hydration First

Before coffee or breakfast, drink 16-20 ounces of room-temperature water. Your body loses 1-2 pounds of water overnight through breathing and sweating, creating mild dehydration that contributes to morning grogginess, headaches, and constipation. Rehydrating immediately upon waking jump-starts metabolism, aids digestion, and improves mental clarity. Add lemon juice if plain water feels boring—the citrus provides vitamin C and makes hydration more appealing.

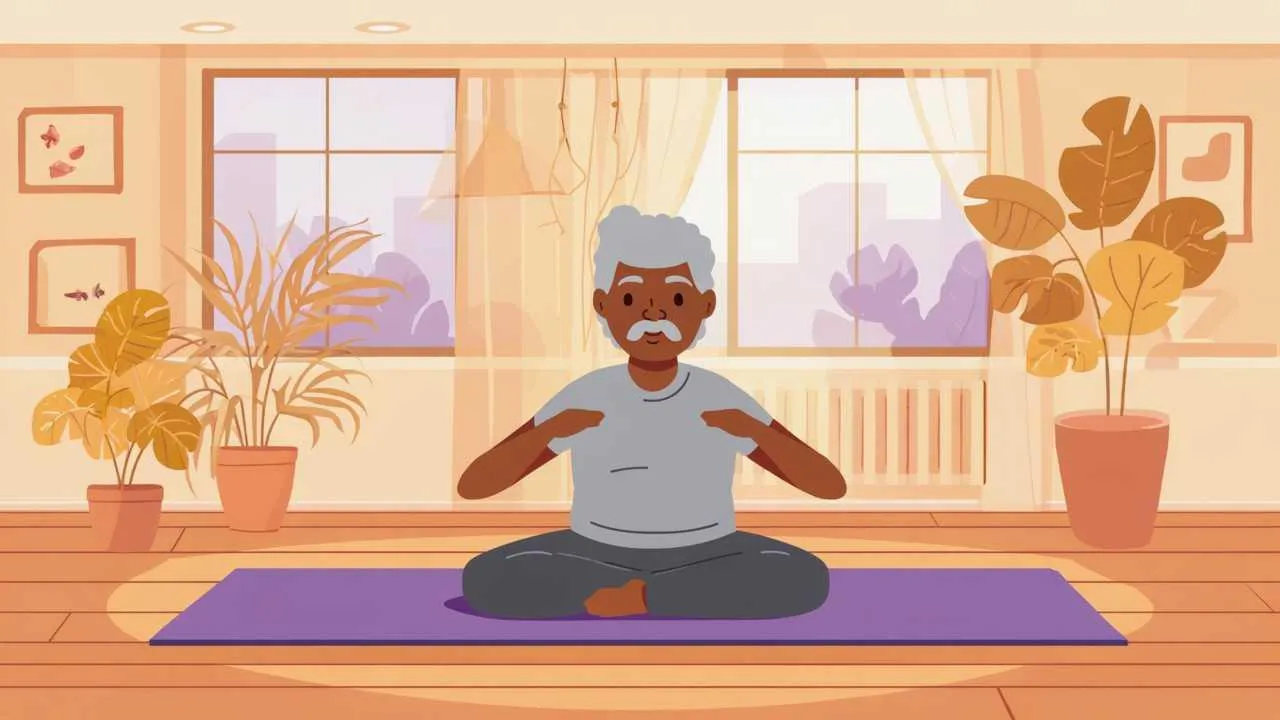

Gentle Morning Movement

Before eating, spend 10-15 minutes on gentle movement awakening your body. This doesn’t mean intense exercise—simple stretching, walking around your home, or basic yoga suffices. Morning movement increases blood flow, reduces stiffness, improves mood through endorphin release, and signals your body that the day has begun.

A simple routine might include: 2 minutes of deep breathing while still in bed, 3 minutes of gentle stretches (arms overhead, side bends, gentle twists), 5 minutes walking around your home or yard, and 3-5 minutes of light calisthenics (wall push-ups, chair squats, standing marches). This 10-15 minute investment dramatically improves how you feel throughout the morning.

Breakfast: Non-Negotiable Foundation

Never skip breakfast—this meal literally “breaks the fast” from overnight sleep, providing fuel for physical and cognitive function. Skipping breakfast is linked to worse cognitive performance, mood problems, increased fall risk, and poorer nutritional status in seniors. Aim for 300-400 calories combining protein, complex carbohydrates, and healthy fats.

Excellent senior breakfast options include: oatmeal with berries, nuts, and Greek yogurt; whole grain toast with avocado and eggs; smoothies with protein powder, banana, spinach, and almond butter; or cottage cheese with fruit and whole grain crackers. Prepare some elements the night before (overnight oats, pre-cut fruit) to simplify morning preparation when you’re less energetic.

Morning Mental Activation

After breakfast, engage in 20-30 minutes of mentally stimulating activity before passive entertainment. This might include: reading a book chapter or newspaper, completing crossword or Sudoku puzzles, writing in a journal, learning a new language through apps like Duolingo, or working on hobbies requiring concentration. Morning mental activity capitalizes on your brain’s peak alertness post-sleep and post-breakfast.

Personal Care and Dressing

Complete personal hygiene and get fully dressed every morning, even if you’re not leaving home. Staying in pajamas all day correlates strongly with depression and low motivation. Getting dressed signals your brain that the day has officially begun and you’re ready for activities. Shower or bathe, dress in clean clothes appropriate for your planned activities, and attend to grooming (teeth, hair, face care). This routine maintains self-respect and readiness for unexpected visitors or spontaneous opportunities.

Visual Art by Artani Paris

Structuring Productive Midday Hours

The middle hours of your day (roughly 9 AM to 3 PM) provide prime opportunities for activities requiring energy, focus, and social interaction. Most seniors experience peak energy and alertness during these hours, making them ideal for demanding tasks, exercise, appointments, and social engagement.

Physical Activity: The Non-Negotiable Priority

Schedule 30-60 minutes of physical activity every day, ideally mid-morning (10-11 AM) when your body temperature rises and muscles are warmer. Physical activity doesn’t require gym memberships or expensive equipment—walking, gardening, dancing, chair exercises, or online workout videos all count. The key is movement intensity appropriate for your fitness level performed consistently.

A balanced weekly exercise routine includes: cardiovascular activity (brisk walking, swimming, cycling) 150 minutes weekly in 30-minute sessions five days; strength training (resistance bands, weights, bodyweight exercises) 2-3 times weekly for 20-30 minutes; flexibility work (stretching, yoga, tai chi) 15-20 minutes daily; and balance exercises (standing on one foot, heel-to-toe walking, standing from seated without hands) 10 minutes three times weekly.

Make exercise appointments with yourself, treating them as seriously as doctor visits. Schedule specific times and activities: “Monday 10 AM: 30-minute neighborhood walk; Tuesday 10 AM: strength training video; Wednesday 10 AM: senior yoga class.” This removes daily decision-making about whether to exercise—it’s simply what you do at that time. Exercise with friends or join classes for social accountability making you less likely to skip.

Productive Tasks and Errands

Handle demanding tasks requiring focus, energy, or travel during mid-morning to early afternoon when you’re most alert. This might include: paying bills and managing finances, scheduling and attending medical appointments, grocery shopping and meal preparation, household maintenance and cleaning, computer work and correspondence, or research and planning for trips or purchases.

Batch similar tasks together for efficiency. Designate specific days for specific categories: Monday for financial tasks (reviewing accounts, paying bills), Tuesday for medical appointments and health-related tasks, Wednesday for grocery shopping and meal prep, Thursday for household cleaning and maintenance, Friday for personal projects and hobbies. This batching creates predictable patterns reducing mental load and decision fatigue.

Lunch: Fueling Afternoon Energy

Eat lunch at a consistent time daily (typically 12-1 PM) to maintain stable blood sugar and energy levels. Lunch should be your substantial meal if you follow traditional Mediterranean eating patterns (large breakfast, substantial lunch, light dinner) associated with better health outcomes for seniors. Aim for 400-500 calories with protein, vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats.

Excellent lunch options include: grilled chicken or fish with roasted vegetables and quinoa; large salads with beans, avocado, nuts, and olive oil dressing; soup and sandwich combinations with whole grain bread; or leftovers from previous evening’s dinner. Avoid heavy, greasy foods causing afternoon sluggishness—stick with lighter proteins, plenty of vegetables, and moderate portions.

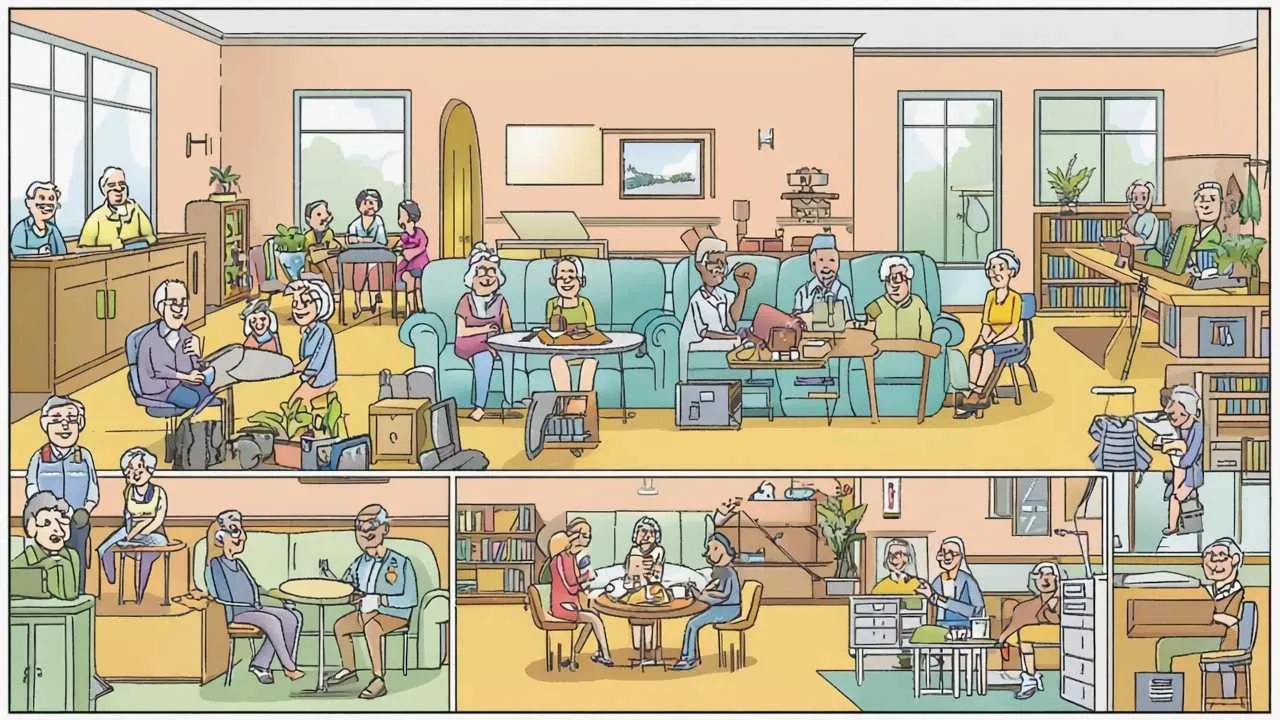

Social Connection Time

Schedule regular social activities during midday hours when friends are available and you have energy for interaction. This might include: weekly coffee or lunch dates with friends, book clubs or hobby groups, volunteer work, senior center activities, phone or video calls with family, or organized outings and day trips.

Treat social commitments as seriously as medical appointments—put them on your calendar and honor them even when you don’t feel like going. Often, the effort of getting out the door is the hardest part, and you’ll enjoy yourself once there. Social isolation accelerates cognitive decline and increases mortality risk as much as smoking 15 cigarettes daily—making social connection a crucial health behavior, not optional luxury.

| Time Block | Activity Type | Duration | Examples | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6:30-8:30 AM | Morning Routine | 2 hours | Wake, hydrate, exercise, breakfast, personal care | Physical & mental activation |

| 8:30-10:00 AM | Mental Stimulation | 1.5 hours | Reading, puzzles, learning, hobbies | Cognitive engagement |

| 10:00-11:30 AM | Physical Activity | 1.5 hours | Exercise class, walking, gardening | Physical health |

| 12:00-1:00 PM | Lunch & Rest | 1 hour | Nutritious meal, brief relaxation | Refueling, digestion |

| 1:00-3:00 PM | Productive Tasks | 2 hours | Errands, appointments, projects | Accomplishment |

| 3:00-5:00 PM | Personal Time | 2 hours | Hobbies, relaxation, social calls | Enjoyment, connection |

| 5:00-6:30 PM | Dinner Prep & Meal | 1.5 hours | Cooking, eating, cleanup | Nutrition, routine |

| 6:30-9:00 PM | Evening Wind-Down | 2.5 hours | Light activities, entertainment, prep for bed | Relaxation, sleep prep |

Balancing Afternoon Rest and Activity

Afternoon hours (roughly 2-5 PM) often bring energy dips, particularly after lunch. Rather than fighting this natural rhythm, design your routine accommodating lower energy while maintaining engagement and avoiding the trap of excessive television or napping.

The Strategic Nap: When and How

Short naps benefit many seniors, but timing and duration matter enormously. If you nap, limit it to 20-30 minutes maximum and complete it before 3 PM. Longer naps or those taken later interfere with nighttime sleep, creating vicious cycles of poor sleep and daytime drowsiness. Set an alarm—even “just closing my eyes for a moment” often extends beyond intended times.

The ideal nap duration is 20 minutes—long enough to feel refreshed but short enough to avoid entering deep sleep stages that cause grogginess upon waking. Find a comfortable chair or couch rather than your bed (which your brain associates with nighttime sleep). Keep the room moderately lit rather than completely dark, and sit semi-upright rather than lying fully flat. These strategies make waking easier and maintain the distinction between naps and nighttime sleep.

Not everyone needs or benefits from naps. If you sleep well at night and maintain afternoon energy, skip napping entirely. If you nap but still feel tired or struggle with nighttime sleep, eliminate naps for two weeks to see if nighttime sleep improves. Many seniors discover that pushing through afternoon tiredness with light activity rather than napping leads to better nighttime sleep and more stable daily energy.

Quiet but Engaged Afternoon Activities

Afternoon hours suit less demanding activities that maintain engagement without requiring peak energy. This might include: hands-on hobbies (knitting, woodworking, puzzles, model building), gentle creative activities (coloring, simple crafts, scrapbooking), light reading (magazines, light fiction, inspirational books), telephone or video calls with family and friends, or preparation for next day’s activities (meal planning, laying out clothes, reviewing calendar).

Avoid passive activities becoming your entire afternoon. One hour of television or social media scrolling is fine, but three hours of screen time erodes physical and mental health. If you find yourself defaulting to excessive passive entertainment, schedule specific afternoon activities creating structure: Tuesday 2 PM is puzzle time, Wednesday 3 PM is craft hour, Thursday 2:30 PM is your weekly call with your daughter.

Light Physical Movement

Combat afternoon sluggishness with light movement every hour. Set timers reminding you to stand, stretch, and walk for 5 minutes hourly. This regular movement prevents stiffness, improves circulation, maintains alertness, and accumulates to meaningful daily activity totals. Simple movements like walking to check the mail, watering plants, doing light stretches, or dancing to a favorite song for a few minutes can transform your afternoon energy.

Preparation and Planning Time

Use afternoon hours for next-day preparation reducing morning stress. This might include: laying out tomorrow’s clothes, preparing breakfast ingredients (overnight oats, pre-cut fruit), reviewing tomorrow’s appointments and commitments, preparing or defrosting components for tomorrow’s dinner, or organizing items needed for morning activities.

Evening meal preparation can begin in afternoon—chopping vegetables, marinating proteins, setting the table. This distribution of tasks prevents the stress of cooking entire meals when you’re tired later. Many seniors find that 20-30 minutes of afternoon meal prep makes evening dinner preparation quick and stress-free.

Creating Relaxing Evening Routines

Evening routines signal your body and mind that the active day is ending and sleep approaches. The key is gradual wind-down through progressively calming activities, avoiding stimulating screens and activities close to bedtime.

Dinner: Light and Early

Eat dinner 3-4 hours before bedtime, typically between 5:30-6:30 PM for most seniors. This timing allows digestion before lying down, preventing heartburn and sleep disruption. Late heavy meals interfere with sleep quality—your body should focus on rest and repair during sleep, not digesting large meals.

Evening meals should be lighter than breakfast and lunch, emphasizing easily digestible proteins and vegetables with moderate portions. Avoid heavy, greasy, or spicy foods that can cause indigestion. Good dinner options include: grilled fish or chicken with steamed vegetables, omelets with whole grain toast and salad, soups with whole grain bread, or light pasta with vegetables and lean protein. Limit fluid intake to prevent nighttime bathroom trips disrupting sleep.

Post-Dinner Light Activity

A brief 10-15 minute walk after dinner aids digestion and provides additional daily movement. This doesn’t need to be strenuous—a gentle stroll around your yard or neighborhood suffices. If weather or mobility prevents outdoor walking, walk around your home or do gentle stretches. This post-dinner movement prevents the sluggishness that comes from sitting immediately after eating and prepares your body for evening relaxation.

Meaningful Evening Activities

The hours between dinner and bedtime (typically 6:30-9:00 PM) should include activities you enjoy that relax rather than stimulate. This might include: reading for pleasure, gentle hobbies (knitting, jigsaw puzzles, adult coloring books), listening to music or audiobooks, light conversation with spouse or phone calls with family, watching favorite television shows (limit to 1-2 hours), playing card games or board games, or journaling about your day.

Avoid stimulating activities close to bedtime: intense exercise, heated discussions or debates, paying bills or dealing with stressful paperwork, watching disturbing news or intense dramas, or working on complex problems requiring concentration. These activities increase alertness when you want the opposite effect.

Screen Time Management

Limit screen exposure (television, computers, tablets, phones) in the 1-2 hours before bed. Screens emit blue light suppressing melatonin production and delaying sleep onset. If you must use screens late evening, enable night mode/blue light filters reducing blue light exposure. Better yet, replace evening screens with non-digital activities—reading physical books, listening to music, or conversing with family.

Avoid scrolling social media or watching news close to bedtime. Both tend to be stimulating or stressful, activating your mind when you want calmness. If you enjoy television evening, watch light content (comedies, nature shows, cooking programs) rather than intense dramas, horror, or upsetting news.

Bedtime Preparation Routine

Create a consistent 30-45 minute bedtime routine signaling your body that sleep approaches. This routine should follow the same sequence nightly, training your brain to recognize sleep preparation. A sample routine might include: 9:00 PM – light snack if hungry (banana, small bowl of cereal, warm milk); 9:15 PM – personal hygiene (brush teeth, wash face, night medications); 9:30 PM – prepare bedroom (adjust temperature, lay out tomorrow’s clothes); 9:40 PM – relaxation activity (reading, gentle stretches, meditation); 10:00 PM – lights out.

Maintain consistent bedtime within 30 minutes nightly. Most seniors need 7-8 hours sleep, so calculate bedtime based on desired wake time. If you wake at 7 AM and need 7.5 hours sleep, aim for 11:30 PM bedtime. Consistency strengthens sleep quality far more than occasionally “catching up” on lost sleep.

| Activity Category | Recommended Daily Time | Best Time of Day | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Exercise | 30-60 minutes | Mid-morning | Walking, swimming, strength training, yoga |

| Mental Stimulation | 60-90 minutes | Morning & afternoon | Reading, puzzles, learning, hobbies |

| Social Connection | 30-60 minutes | Midday | Calls, visits, classes, volunteer work |

| Meals & Prep | 3-4 hours total | Morning, noon, evening | Breakfast, lunch, dinner with prep time |

| Personal Care | 60-90 minutes | Morning & evening | Hygiene, grooming, dressing |

| Rest & Relaxation | 2-3 hours | Afternoon & evening | Reading, TV, hobbies, meditation |

| Sleep | 7-8 hours | Night | Consistent bedtime and wake time |

Building Flexibility Into Your Routine

While routine provides valuable structure, excessive rigidity creates stress and prevents enjoying spontaneous opportunities. The goal is flexible structure—consistent patterns you usually follow but can adjust without anxiety when circumstances change.

Core vs. Flexible Activities

Distinguish between core activities requiring consistency (wake time, meals, exercise, medication schedules, bedtime) and flexible activities that can shift based on circumstances (specific hobbies, social activities, errands). Core activities form your routine’s foundation—these happen at roughly the same times daily regardless of other factors. Flexible activities fill remaining time and can be rearranged as needed.

For example, waking at 7 AM, eating breakfast at 8 AM, exercising at 10 AM, and going to bed at 10:30 PM might be core elements. But whether you read, do puzzles, or work on crafts mid-afternoon is flexible based on mood and circumstances. This distinction prevents feeling like you’ve “failed” your routine when life intervenes.

Planning for Disruptions

Accept that disruptions are inevitable—doctor appointments, family visits, illness, weather emergencies, or simply days you don’t feel like following your usual routine. Rather than abandoning structure entirely during disruptions, identify minimum viable routines maintaining crucial elements while accommodating changes.

A minimum viable routine might include: wake at usual time (even if you don’t leave bed immediately), eat three meals at roughly regular times (even if simpler than usual), move your body for at least 15 minutes (even if just walking around your home), and maintain your regular bedtime (even if you adjust other evening activities). These minimums prevent complete routine collapse during challenging periods.

Weekly Rhythm vs. Daily Uniformity

Rather than making every day identical, create weekly rhythms with different focus areas on specific days. This variation prevents boredom while maintaining structure. You might designate Monday for errands and appointments, Tuesday for social activities, Wednesday for home projects, Thursday for hobbies and creative time, Friday for meal planning and preparation, Saturday for family time, and Sunday for relaxation and planning the week ahead.

This weekly rhythm provides structure without monotony. You know generally what type of activities happen on which days, but specific activities within those categories can vary. This approach accommodates the reality that you don’t always feel like doing the same things while preventing completely unstructured days.

Seasonal Adjustments

Recognize that your routine will and should change with seasons. Winter routines might emphasize indoor activities, earlier bedtimes, and different exercise options than summer routines featuring outdoor activities, later sunsets, and gardening. Adjust wake times slightly with daylight changes—waking in darkness all winter can be depressing and difficult.

Plan seasonal transition periods when you consciously adjust your routine to accommodate changing conditions. As fall approaches, gradually shift outdoor activities indoors and adjust wake times to align with earlier sunrises. These gradual adjustments feel natural rather than sudden disrupting changes.

Overcoming Common Routine Challenges

Establishing and maintaining routines presents specific challenges for seniors. Understanding common obstacles and strategies for overcoming them increases your chances of successful routine implementation.

Low Motivation and Depression

Depression is the most significant barrier to routine maintenance. When depressed, everything feels pointless and effortful. The catch-22 is that routine helps alleviate depression, but depression makes following routine nearly impossible. If you suspect depression, seek professional help immediately—routine alone won’t cure clinical depression requiring medical intervention.

For mild to moderate motivation challenges, use external accountability. Tell friends or family about your routine goals and ask them to check in regularly. Join classes or groups at scheduled times—you’re more likely to show up when others expect you. Use technology like reminder apps, fitness trackers, or even simple calendar alerts prompting you to do specific activities at designated times.

Start extraordinarily small if you’re struggling. Rather than implementing a complete routine, choose one tiny behavior to do consistently for two weeks—perhaps just making your bed every morning or taking a 5-minute walk after breakfast. Once that becomes automatic, add another small behavior. This incremental approach builds momentum without overwhelming you.

Chronic Pain and Fatigue

Physical limitations from arthritis, chronic pain, or fatigue require routine adaptations but don’t eliminate routine benefits. Design routines accommodating your energy patterns—if you’re most energetic mornings, schedule demanding activities then and save gentler activities for afternoons. If pain peaks certain times daily, plan around those periods.

Build in adequate rest without allowing rest to consume entire days. Alternate active and rest periods—30 minutes of activity followed by 15 minutes of rest prevents both overexertion and complete inactivity. Chair-based exercises, seated hobbies, and activities requiring minimal physical effort still provide structure and engagement when standing and walking are challenging.

Communicate with your doctor about pain and fatigue patterns. Sometimes medication timing adjustments, different treatment approaches, or addressing underlying causes significantly improves energy levels and pain management, making routine maintenance easier. Don’t assume chronic fatigue is just “part of aging”—it often indicates treatable conditions.

Cognitive Challenges

For those experiencing memory issues or early cognitive decline, routine becomes even more important while simultaneously harder to maintain independently. External supports become crucial—written schedules posted prominently, medication organizers with alarms, phone reminders for appointments and activities, and involvement of family or caregivers in routine maintenance.

Simplify routines to essential elements when cognitive challenges make complex schedules overwhelming. Focus on core activities (wake, eat, move, sleep) rather than elaborate schedules. Use visual cues—pictures showing the sequence of morning routine steps, labels on cabinet doors showing contents, clocks showing not just time but activities typically done at those times.

Consistency becomes paramount—doing the same things in the same order at the same times creates patterns your brain can follow even when memory falters. The more automatic your routine becomes, the less conscious thought required to maintain it.

Living with Others

Coordinating routines with spouse, family, or roommates requires communication and compromise. Discuss ideal routines with household members, identifying shared activities (meals, evening time) and independent activities (exercise, hobbies). Respect each other’s routine needs—if one person is a morning person who wakes at 6 AM and the other prefers sleeping until 8 AM, the early riser should move quietly and keep bedroom lights off.

Create shared schedule systems—wall calendars, shared digital calendars, or simple written schedules posted in common areas. This transparency prevents conflicts over shared spaces and times. Negotiate challenging areas—if one person wants quiet evenings while the other enjoys television, perhaps the TV watcher uses headphones or watches in a different room certain evenings.

| Challenge | Impact | Solutions | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Motivation | Skipping activities, routine collapse | External accountability, start small, rewards | Moderate (65%) |

| Chronic Pain | Activity avoidance, inconsistency | Adapt activities, rest periods, pain management | Good (75%) |

| Poor Sleep | Morning fatigue, timing disruption | Sleep hygiene, consistent schedule, doctor consult | Very Good (80%) |

| Social Isolation | Lack of external structure, loneliness | Join groups, schedule regular social contact | Very Good (85%) |

| Weather/Seasonal | Activity limitations, mood changes | Indoor alternatives, seasonal adjustments, light therapy | Good (70%) |

| Health Setbacks | Routine disruption, recovery challenges | Minimum viable routine, gradual rebuilding | Moderate (60%) |

Real Success Stories

Case Study 1: Phoenix, Arizona

Dorothy L. (71 years old)

After retiring from 35 years teaching elementary school, Dorothy struggled profoundly with the sudden loss of structure that had defined her adult life. Within three months of retirement, she found herself staying in pajamas until noon, eating irregularly, watching television 6-8 hours daily, and feeling increasingly depressed and purposeless. She gained 18 pounds, stopped seeing friends, and began experiencing alarming memory lapses her doctor attributed partly to depression and social isolation.

Her daughter, concerned about Dorothy’s rapid decline, suggested they work together to create a daily routine incorporating elements Dorothy had enjoyed throughout her life—reading, walking, crafting, and social connection. They started with just three non-negotiable commitments: wake by 7:30 AM, walk 20 minutes after breakfast, and attend weekly craft group at the senior center on Thursdays.

Dorothy gradually expanded her routine over six months, adding morning reading time, regular meal schedules, afternoon craft projects, evening phone calls with friends, and consistent 10 PM bedtime. The structure transformed her mental and physical health dramatically. She reported feeling like “myself again” and having purpose and accomplishment each day even without work responsibilities.

Results:

- Depression scores (PHQ-9) improved from 16 (moderate-severe depression) to 5 (minimal symptoms) over 6 months

- Lost 15 of the 18 pounds gained post-retirement through regular meal timing and daily walking

- Sleep quality improved significantly—falling asleep in average 12 minutes versus previous 45+ minutes, sleeping through the night 5-6 nights weekly versus 1-2

- Social contacts increased from 1-2 weekly interactions to 8-10, including weekly craft group, twice-weekly walking partner, and regular phone calls

- Memory concerns resolved completely—doctor attributed previous lapses to depression and poor sleep rather than cognitive decline

“I didn’t realize how much I needed structure until it disappeared. I thought retirement would be this wonderful freedom, but it felt more like drowning. My routine saved me—I wake up now knowing what my day looks like, feeling like I have purpose even though I’m not working anymore. The structure doesn’t feel restrictive; it feels comforting and empowering.” – Dorothy L.

Case Study 2: Minneapolis, Minnesota

Harold and Joyce M. (both 68 years old)

This retired couple found retirement straining their 42-year marriage unexpectedly. With Harold home all day after retiring from engineering management and Joyce already retired from nursing, they struggled with conflicting daily rhythms, different activity preferences, and constant togetherness after decades of separate workdays. They bickered constantly about meal times, television control, and household tasks, with both feeling their personal space and independence had vanished.

Their marriage counselor suggested creating individual routines with designated shared and independent times. They scheduled morning coffee together (7-8 AM), but Harold then went for long walks while Joyce did morning yoga and reading. They reconvened for lunch (12:30 PM), then pursued separate afternoon activities—Harold woodworking in the garage, Joyce meeting friends or working on quilting projects. They shared dinner preparation and meals (5:30-7 PM) followed by independent evening activities until 8:30 PM when they watched one show together before bed.

This structured approach to shared and independent time dramatically reduced conflict and increased appreciation for time together. They stopped feeling resentful about lost independence while maintaining connection through intentional shared periods. The routine honored both partners’ needs for autonomy and companionship.

Results:

- Marital satisfaction scores increased from 4.2/10 to 8.1/10 over 4 months as measured by Dyadic Adjustment Scale

- Conflict frequency decreased from multiple daily arguments to 1-2 minor disagreements weekly

- Both partners pursued individual interests they’d abandoned—Harold completed 6 woodworking projects he’d dreamed about for years; Joyce finished 3 quilts and joined two social groups

- Physical health improved for both—Harold lost 12 pounds through daily walking (total 8 miles daily); Joyce’s blood pressure decreased from 148/92 to 128/78 through regular yoga and stress reduction

- They reported feeling “like we’re partners again instead of irritating roommates”

“We almost got divorced after 42 years together because retirement made us smother each other. The structured routine—knowing when we have couple time and when we have individual time—saved our marriage. We appreciate our time together so much more now because it’s not forced 24/7 togetherness. The routine gave us both freedom and connection simultaneously.” – Joyce M.

Case Study 3: Richmond, Virginia

Marcus T. (74 years old)

Living alone after his wife’s death three years prior, Marcus struggled with motivation and purpose. Days blurred together without structure—he’d stay up until 2-3 AM watching television, sleep until 10-11 AM, eat whatever was easiest (often just cereal or takeout), and spend most days in his recliner feeling increasingly isolated and depressed. His adult children, who lived in different states, worried about his declining health but couldn’t be physically present daily to provide support and accountability.

His daughter researched senior services and enrolled Marcus in a structured senior day program three days weekly (Monday, Wednesday, Friday 9 AM-3 PM). The program required him to wake early, get dressed, and be ready for transportation at 8:45 AM. The program included exercise classes, social activities, lunch, educational programs, and hobby workshops. This external structure for three days weekly gave Marcus a foundation to build additional routine around.

On program days, Marcus naturally fell into better patterns—going to bed earlier to wake for 8:45 pickup, eating breakfast before leaving, feeling energized from activities and social interaction. He gradually extended routine elements to non-program days—maintaining the same wake and bedtimes, eating regular meals, doing light exercise, and scheduling activities (grocery shopping, doctor appointments, hobbies) during afternoon hours.

Results:

- Sleep patterns normalized—falling asleep by 10:30 PM most nights and waking naturally around 7 AM without alarms versus previous 2-3 AM bedtimes and 10-11 AM wake times

- Lost 22 pounds over 8 months through regular meals, program exercise, and reduced late-night eating

- Made 5 genuine friendships at the program leading to additional social activities outside program hours

- Volunteered to help with program’s woodworking workshop, giving him renewed sense of purpose and expertise to share

- Depression scores improved from 19 (moderate-severe) to 8 (mild) over 8 months; doctor reduced antidepressant medication under supervision

“I resented my daughter for signing me up for that senior program without asking me first—I thought it was ‘for old people’ and I wasn’t that far gone. But it literally saved my life. Having somewhere to be three days a week got me out of my recliner and back into the world. The routine I built around those program days gave structure to the rest of my week. I have friends again, things to look forward to, reasons to get out of bed. I’m living instead of just existing.” – Marcus T.

Frequently Asked Questions

How strict should my routine be? Can I make exceptions?

Routines should provide structure without becoming rigid prisons. Aim for 80% consistency—following your routine most days while allowing flexibility for special occasions, health challenges, or simply days you need something different. The key is returning to your routine after exceptions rather than letting single deviations spiral into complete routine abandonment. Core elements like wake time, meals, and bedtime should be most consistent (within 30-60 minutes daily), while specific activities can vary more freely. Think of your routine as guidelines supporting your wellbeing rather than strict rules you’ve failed if you break.

What if I live with someone whose routine conflicts with mine?

Different sleep schedules, activity preferences, and daily rhythms are common sources of friction for couples and housemates. Communication and compromise are essential. Discuss ideal routines with household members and identify areas of flexibility and non-negotiable needs. Create shared schedule systems (wall calendars, shared digital calendars) showing each person’s commitments. Respect each other’s routine needs—morning people should move quietly and keep lights low until afternoon people wake; night owls should use headphones and keep noise down after early risers sleep. Designate certain times as together time and other times as independent time when each person can pursue activities in separate spaces. Consider using different rooms for conflicting activities—one person reads in the bedroom while the other watches TV in the living room.

How long does it take to establish a new routine?

Research shows habit formation takes anywhere from 18 to 254 days depending on complexity and individual factors, with average being 66 days. For routines involving multiple behaviors, expect 2-3 months before they feel automatic rather than requiring conscious effort. Start with 1-2 core behaviors, practice them consistently for 2-3 weeks until they feel natural, then gradually add additional elements. Don’t try implementing a complete routine overnight—this approach overwhelms most people leading to complete abandonment. Instead, build your routine gradually, giving each new element time to become habitual before adding the next. Celebrate milestone markers (one week, two weeks, one month of consistency) to maintain motivation during the establishment period.

What if I have irregular medical appointments disrupting my routine?

Frequent medical appointments are common for many seniors and require routine flexibility without routine abandonment. Schedule appointments consistently (all morning appointments or all afternoon appointments when possible) minimizing disruption. Build appointment days into your weekly rhythm—perhaps Wednesday is always “appointment day” when your routine shifts to accommodate medical visits. Maintain core routine elements even on appointment days—wake at usual time, eat breakfast, take medications, maintain evening routine and bedtime. Consider appointments as replacing one activity block rather than destroying your entire day’s structure. Many seniors find that organizing all appointments into one or two days weekly allows other days to follow consistent routines without interruption.

How do I maintain my routine when traveling or during holidays?

Travel and holidays inevitably disrupt routines, but you can maintain core elements even in new environments. Stick to usual wake and bedtimes as much as possible—this prevents jet lag and maintains sleep quality. Pack medications in carry-on bags and take them at scheduled times using phone alarms if needed. Build in daily physical activity even if different from home routine—hotel gym workouts, walking tours, swimming in hotel pools. Maintain meal timing even if food choices differ. The goal isn’t perfect routine replication but rather maintaining enough structure that returning to full routine afterward feels natural rather than starting from scratch. Many seniors find that maintaining 50% of their normal routine during travel is sufficient to prevent complete disruption while still enjoying vacation flexibility.

Is it too late to start a routine if I’ve been retired for years without one?

It’s never too late to establish beneficial routines. While forming new habits becomes slightly harder with age, the benefits remain substantial regardless of when you start. Many seniors successfully implement routines years into retirement, experiencing dramatic improvements in sleep, mood, energy, and overall wellbeing. Start from wherever you are now—don’t waste energy regretting years without routine. Begin with one small, achievable behavior (making your bed daily, eating breakfast at a consistent time) and build gradually. If you’ve functioned for years without routine, you’re not broken—you simply haven’t yet discovered how much better you can feel with structure. Give yourself 90 days of honest effort before deciding whether routines benefit you. Most seniors who try report they wish they’d started sooner.

What if depression makes following any routine seem impossible?

If clinical depression prevents you from establishing routine despite genuine effort, you need professional help—routine alone won’t cure depression requiring medical intervention. However, routine can be powerful adjunct treatment. Start extraordinarily small—literally one minute of one activity daily. Success with tiny behaviors builds momentum and self-efficacy. Use external accountability—tell someone your one-minute goal and have them check daily whether you completed it. Consider enrolling in structured programs (senior centers, day programs, classes) providing external structure when internal motivation fails. Discuss with your doctor whether medication adjustments might improve energy and motivation enough to begin routine establishment. Remember that depression lies—it tells you nothing matters and nothing will help. These thoughts are symptoms, not truth. Routine establishment, even minimal routine, often provides the foundation allowing other depression treatments to work more effectively.

How do I balance routine with spontaneity and fun?

Routine and spontaneity aren’t opposites—in fact, good routines create space for spontaneity by handling essential activities efficiently, freeing time and energy for unplanned opportunities. Designate specific times as “unscheduled” for spontaneous activities—perhaps Saturday afternoons have no routine commitments, leaving you free for whatever appeals that day. When spontaneous opportunities arise (friend invites you to lunch, unexpected nice weather perfect for outdoor activity), adjust flexible routine elements while maintaining core elements. The goal is routine as foundation supporting rich, varied life rather than routine as rigid prison preventing enjoyment. Many seniors find that routine actually enables spontaneity because they feel better, have more energy, and manage time well enough that they can say yes to unexpected opportunities without anxiety about neglecting important activities.

Should I have different weekend routines versus weekday routines?

This depends on your personal preferences and social circumstances. Some seniors benefit from identical daily routines seven days weekly, finding this consistency simplifies life and optimizes health habits. Others prefer slight weekend variations—sleeping 30-60 minutes later, more relaxed morning routines, different social activities—providing variety while maintaining overall structure. The critical elements (wake time within 1-2 hours of weekday wake time, regular meals, bedtime consistency) should remain relatively stable even if weekend activities differ from weekdays. Avoid extreme differences—sleeping until noon on weekends after waking at 7 AM weekdays—as these patterns disrupt circadian rhythms and create “social jet lag” making Monday mornings brutal. Find balance between beneficial consistency and enjoyable variety that suits your life and preferences.

What if I’m a natural night owl but everyone says seniors should wake early?

While sleep patterns tend to shift earlier with age due to biological changes, individual chronotypes (whether you’re naturally a morning person or night owl) persist throughout life. If you’re a lifelong night owl who functions best with later wake and bedtimes, honor your biology rather than forcing yourself into a “standard senior schedule” causing sleep deprivation and misery. The key is consistency within your natural rhythm—if you naturally sleep 11 PM-7 AM or midnight-8 AM and feel well-rested on this schedule, maintain it. Problems arise not from specific times but from inconsistency and insufficient sleep duration. If your night owl tendencies lead to 2 AM bedtimes, noon wake times, and resulting social isolation (missing morning activities and appointments), work gradually toward earlier times while respecting you’ll never be a 6 AM riser. Shift bedtime and wake time 15 minutes earlier every few days until reaching a schedule balancing your chronotype with practical life demands.

Action Steps to Build Your Balanced Routine

- Track your current routine for one week without changing anything, noting wake and bedtimes, meal times, activities, energy levels, and mood to establish your baseline patterns and identify problems

- Choose your ideal wake time based on natural chronotype and life demands, then calculate bedtime allowing 7-8 hours sleep, and commit to this schedule within 30 minutes daily for two weeks before adding other changes

- Plan three meals daily at consistent times (breakfast within 1 hour of waking, lunch 4-5 hours later, dinner 5-6 hours after lunch) and prepare simple menus for the first week removing decision fatigue

- Schedule 30 minutes of physical activity daily at a specific time (ideally mid-morning when energy peaks) and choose activities you actually enjoy rather than what you think you “should” do

- Identify one social connection activity weekly (class, group, standing coffee date) providing external accountability and regular human interaction regardless of daily motivation fluctuations

- Create a simple written routine listing your intended schedule for morning, midday, afternoon, and evening, posting it somewhere visible until patterns become automatic

- Establish a 30-45 minute bedtime preparation routine you’ll follow nightly including personal hygiene, bedroom preparation, and relaxing activity signaling your body that sleep approaches

- Set phone reminders for key routine activities during the first month (wake time alarm, meal times, exercise time, bedtime preparation start) until behaviors become habitual

- Tell one trusted friend or family member about your routine goals and ask them to check in weekly about your consistency, providing external accountability during establishment phase

- Evaluate after 30 days whether your routine improves sleep, energy, mood, and overall life satisfaction, then adjust problem areas rather than abandoning the entire routine if certain elements aren’t working

Disclaimer

This article is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute professional medical, mental health, or therapeutic advice. While research demonstrates benefits of structured daily routines for seniors, individual health needs vary significantly. Consult qualified healthcare providers before beginning new exercise programs, making significant lifestyle changes, or if you experience symptoms of depression or other mental health conditions. Information about health conditions, sleep patterns, and wellness strategies represents general guidance, not medical diagnosis or treatment. What works for one individual may not suit another’s specific circumstances.

Information current as of October 2, 2025. Health recommendations, research findings, and best practices may evolve as new information becomes available. Always verify health information with qualified medical professionals.

Related Articles

- Daily Routines That Bring Balance After Retirement

- Senior Travel Tips: How to Enjoy Stress-Free Journeys

Updated October 2025